The Climbing Community is Imaginary

The science of groups and how to recognise a real community.

This article will join in the chorus of voices that have pointed out that The Climbing Community™ is an illusion.1 The critiques thus far have ranged from polemics to ethnographies to satire and have achieved much in rubbishing this fictional entity. The present article is a somewhat of an extension to one of these, namely There is No Such Thing as The Climbing Community. Here we will draw on scientific evidence to demonstrate what The Climbing Community™ really is: a product of imagination, no more real than Father Christmas, Jack Frost or the Easter Bunny.

Firstly, this article will explain the basics of group psychology. Secondly, it will suggest why climbing journalists and brands refer to The Climbing Community™ so much. Thirdly, it discusses what real climbing communities look like. It concludes with some ideas for how we can repopulate our world with real climbing communities.

What is a group?

Without further ado let us jump into the psychology. First, let's establish what exactly a group is:

Groups are more than just a raw collection of people, just as a melody is more than just a raw collection of notes.2

Groups are not simply aggregates, or heaps of people, they are something more than this. Other metaphors illustrating the difference might be:

A mosaic compared to a pile of tiles.

A novel compared to a list of words.

In other words, groups are entities: they have a distinct existence above and beyond that of the individual members of which they are composed, and this existence has an identity of its own. It makes sense to talk about a group — such as a family, a village community or a climbing club — at various points in time and know that you are still referring to the same thing even if the individuals who make up that thing are different at those times.3 The exact opposite of a group would be a random selection of total strangers from the world’s population — this is a mere mathematical set, nothing more.

Four Types of Social Entity

Four types of association emerge spontaneously but consistently when both adults4 and children5 think about how human beings relate to one other.

Intimacy groups: Examples of these are people in a romantic relationship, families, friendship groups, climbing clubs, and local communities. They are ongoing processes, characterized by dynamic relational properties of mutual loyalty, affection and sharing. Such groups are often long lasting and may have barriers to entry and to exit. All members are personally known to each other.

Task groups: such as an airline flight crew, members of a jury, or a student campus committee. These are sets of people who are working together for a common goal. The group exists because there is a job to be done and people are doing it. These groups are ongoing processes based on collaboration, though members likely participate because they are getting something in return. Once again, all members are personally known to each other.

Social categories: these are categories such as females, The French, people with green eyes, Mormons, people who are left-handed, and so on. They are based on the mere sharing of a certain characteristic or identity label. Consequently, social categories are far too large and disconnected to function like groups and rely on a strong centralised leadership hierarchy if they are to act as an effective entity.6 Nonetheless, naive adults and young children will assume that people in the same social category are similar, have shared preferences and common knowledge.7 They also incorrectly assume that people within the same category actually know each other. In other words, they incorrectly identify categories as intimacy groups.

Loose associations: These are extremely short-lived collections of people — such as people waiting at a particular bus stop or an audience watching a film — and collections of people who share a common preference — such people who enjoy classical music, real ale enthusiasts, or people who go climbing. These social entities are characterised by members having few interactions with each other, little to no interdependency, and being easy to enter and exit.

Entitativity

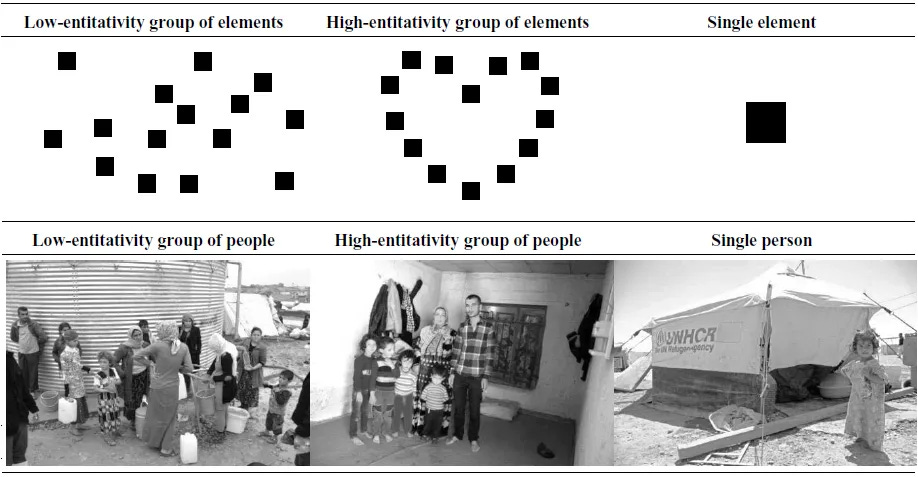

Research into entitativity — the degree to which a collection of individuals is perceived as an entity — indicates that some of these types are more entity-like than others.8 The difference between a collection with low entitativity and a collection with high entitativity is illustrated below.9

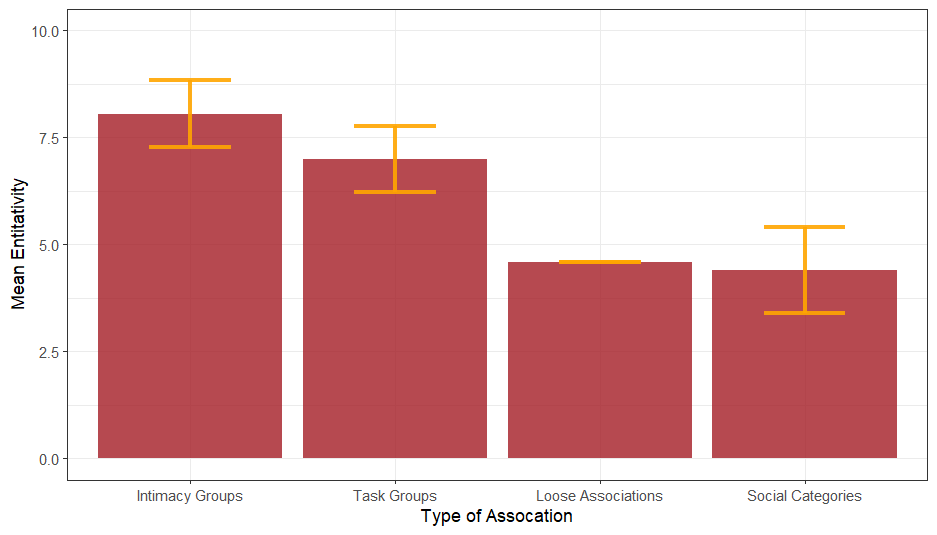

The following graph illustrates the entitativity ratings of each of the four collection types ranging from 1 (not a group at all) to 9 (very much a group).10

As you can see, there is a clear divide between collections that are groups, and collections that are categories. Intimacy and task groups are far more entitative and are thus more likely to be seen to exist above and beyond their individual members. This largely because groups are relational — it is only when a person is participating in the right kind of relationships with other members that he or she can be considered a member of that group.11 In other words, groups are inferred from real existing connections, interdependencies and their consequences.12 Categories, on the other hand, are posited to exist despite members in a category not needing to have any personal connections to one another whatsoever.13

Another significant difference is the needs that membership of each type of association satisfy. Intimacy groups serve needs for connection, attachment and belonging; task groups serve a need for achievement; and categories satisfy a need for identity.14 The meeting of these needs is essential for experiencing happiness, staving off negative emotions, and living a satisfying and meaningful life.15 In a recent video Dave Macleod stated that, in his opinion, connection to other people is a vital contributor to both health and athletic performance. To reiterate: mere category membership cannot yield connection. This will be important later.

A final consideration is that more entitative associations have more powerful social norms,16 members are more likely to engage in groupthink,17 and dissenters are more likely to be punished and ostracised.18 Consequently, if you can frame a social category or loose association as a group — especially as an intimacy group — then any social norms attributed to it will carry more persuasive weight and will be more likely to determine members’ behaviour.19 This too will be important later.

Identification

So how do people relate to social entities? The first of these ways is social identification — feeling as though you are a member of a particular entity. When you identify with a social entity you adopt its roles, norms, and values. For example, identifying as a member of a family might involve providing guidance, support, and protection, doing chores, participating in family rituals and customs, enforcing family standards and norms, and so on. Identifying with a task group entails assuming the required role and adhering to the norms and values essential for the group to accomplish its task.

In contrast to groups, category membership necessitates no interaction between members, and thus it is not immediately apparent how roles, norms, and values for categories are established, let alone enforced.

However, attributing a name or other symbol (e.g. The X Community) to a category increases its perceived entitativity20 and increases the degree to which members identify with and feel a sense of belonging towards it.21 The thought “I am a member of X” allows for the possibility of an idea of what it means to be a good member of X.22 By using a symbol to rebrand a category it becomes possible to assert the existence of norms, values and behaviours for that category.

Once established, identifying members will autonomously enforce these social norms. Even young children will negatively evaluate fellow group members who fail to follow norms and conventions.23 The strength of social norms is such that the behaviour of disliked ingroup members is judged more harshly than that of disliked outgroup members — a phenomenon known as the Black Sheep Effect.24

Fusion

The second way people can relate to social entities is called fusion. This is the degree to which a person incorporates a social entity into their sense of self. This is assessed using the images below. Participants are asked to think about their relationship with a social entity. They are then presented with the images, and are asked for the image which most closely resembles their relationship to that entity.25 A represents no fusion, and E represents strong fusion and concomitant visceral sense of ‘oneness’ with the entity. The more strongly fused someone is the more someone feels as though they are that group and that group is them.26

As an exercise, use the images to reflect on how you perceive your relationship with each of the following entities:

Your family.

Your work colleagues.

A sports team / church or other religious group / local community you participate in.

The category of people with the same hair colour as you.

The category of people who enjoy your favourite food.

The category of people who climb.

The Climbing Community.

Fusion also increases adherence to group norms27 but, unlike mere social identification, identity fusion can cause people to make costly personal sacrifices in order to aid the group,28 to retaliate against those who threaten the group,29 and to enforce norms about group loyalty, the respect of group authority figures, and the preservation of what the group considers sacred.30

An illustrative example of a speech which stresses the entitativity of a group, and induces its members to identify and fuse with it, is that made by King Henry V prior to the Battle of Agincourt in the film The King (2019). See if you can feel any of the intended effects.31

Atomisation and its Cost

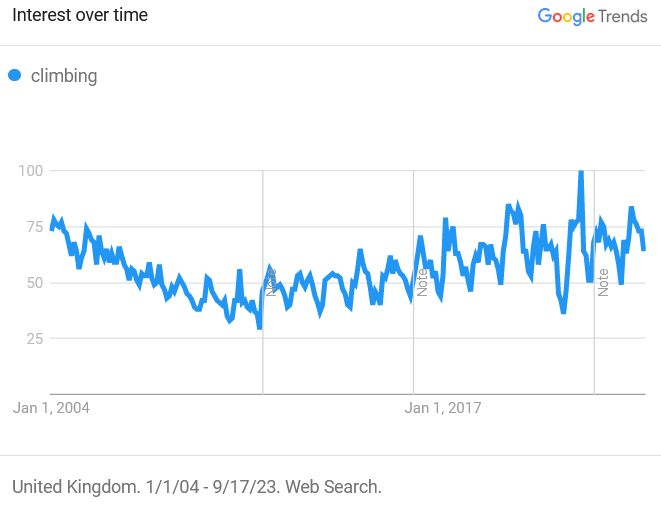

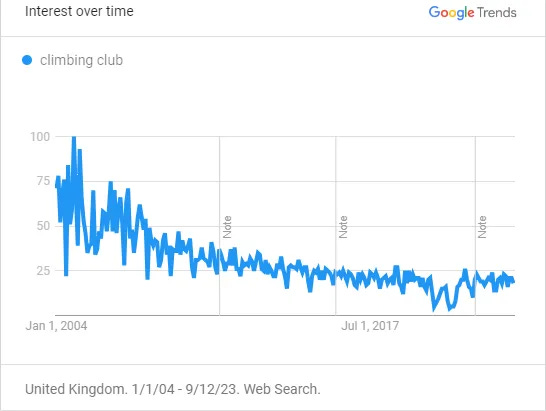

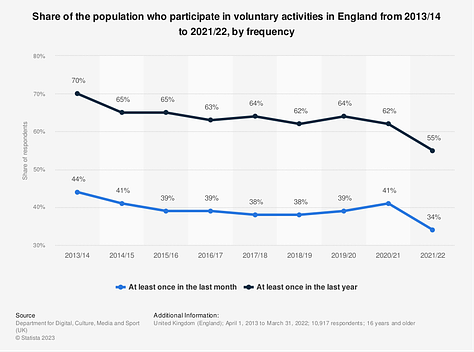

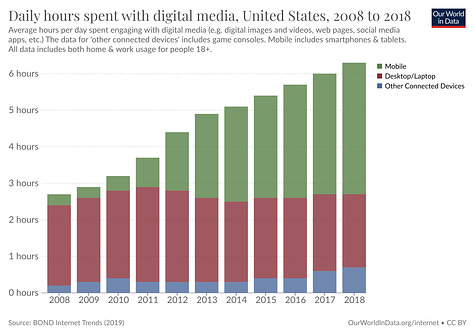

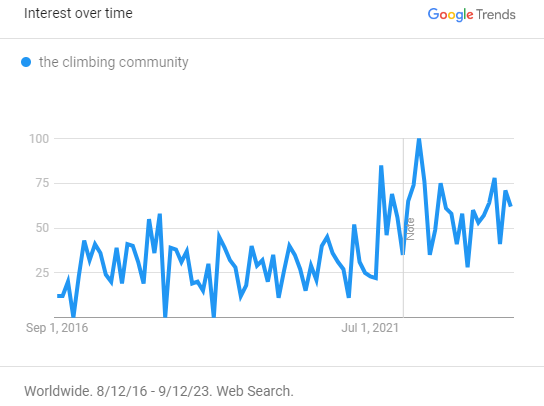

Data from Google Trends shows a persistent decline in interest in climbing clubs, despite interest in climbing being higher than ever.

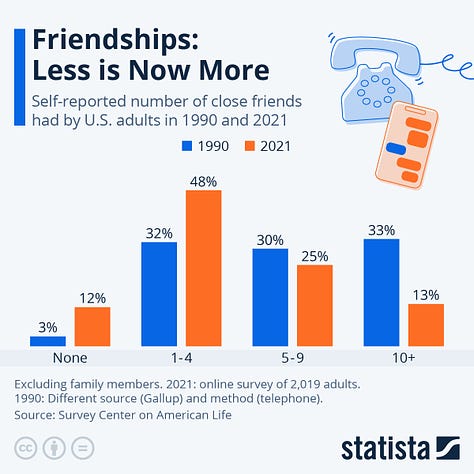

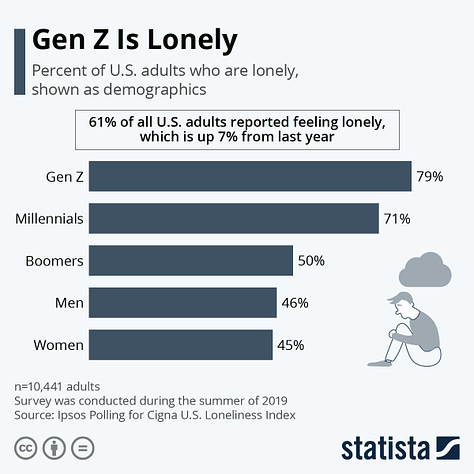

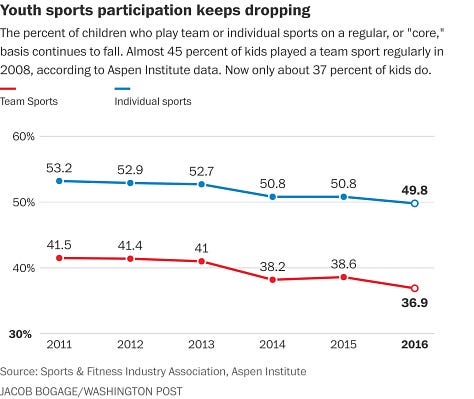

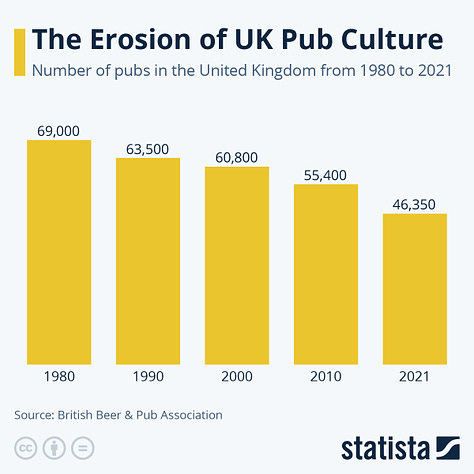

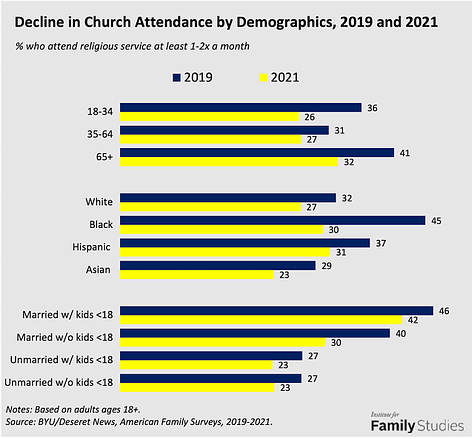

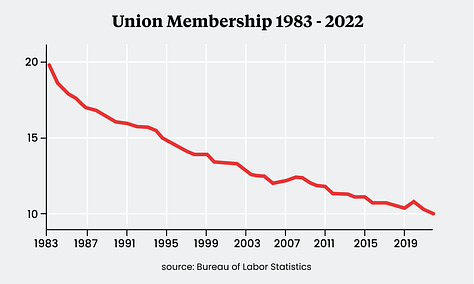

This decline in interest in climbing clubs mirrors declines in other areas of collective life in ‘The West’. Below is a collection of statistics showing declines in participation in groups including sports and clubs, churches, trade unions and voluntary organisations.

Groups such as these are playing an increasingly small part in our lives. As a consequence, we are living more isolated, lonely, parasocial, individualistic and unhappy lives than ever before.32 This process is known as atomisation. Much as an atom can be separated from the molecule to which it belongs, so too we have become split off from groups which in earlier times we would have been part. This has occurred to such an extent that we in the West are significantly less able to perceive groups as entities — seeing them instead as mere collections of individuals.33

Much debate has been had over why this has occurred. Discussion of this is beyond the scope of this article — for our purposes we merely need to observe that this has happened and that it is continuing to worsen.

Loss of social capital, of real communities to participate in and belong to, is associated with greater identification with social categories.34 It is also likely that there has been a concomitant increase in identification/fusion with loose associations too.35 Categories and associations which have been confused and conflated with real communities are known in the academic literature as imagined communities.36 They are imaginary because they lack the relationships, interdependency, intimacy and entitativity that make real communities what they are. If everyone stopped thinking about an imagined community it would simply collapse back into being a category. Theorists Benedict Anderson37 and Jacques Ellul38 attribute the prevalence of imagined communities to the atomised nature of the modern world and the presence of bad actors willing to exploit individuals’ unmet needs to belong.

Marketing and management theorists have long been thinking about how imagined communities can be instantiated and utilised in the sporting domain. Those interested in this may wish to read: Inventing Team Tradition: a Conceptual Model for the Strategic Development of Fan Nations.

The Climbing Community™

Now, let's delve into the concept of 'The Climbing Community'. This symbol is used to refer to the loose association of people who, other than attempting to climb things, need not have anything in common, have ever met, know each other, or have any kind of relationship with each other. As should now be clear: this is not a group, nor is it a community, it is merely a category. Some would argue that it does not exist at all. Even if it does exist in some sense, it would be as the result of confusing a category for an intimacy group and thus be, at the very most, imaginary.39 The Climbing Community™ is real in the same way the Tooth Fairy is real — in both cases, some pretend as if the symbol exists so that others will genuinely believe.

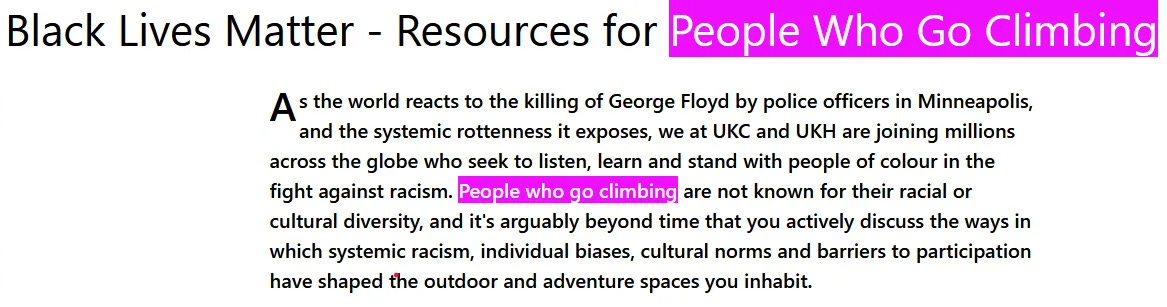

Likewise, The Climbing Community™ is regularly and increasingly deployed by journalists and business owners attempting to transform an unrelated mass of climbers into a collective entity. In explicit terms, they are actively trying to dress a loose association up as a community — i.e., as an intimacy group. This serves four purposes — three of which are outlined below, and the last one will be discussed later.

To appeal to those poor souls who do not belong to any real communities, by providing them with an extremely abstract and attenuated form of attachment, belonging, solidarity and consolation.40

To induce these atomised people into identifying, or fusing their identity, with the fictitious community that has been conjured into existence.

To mobilise these newly identified/fused (but still atomised) individuals in the name of whatever cause a journalist would like to promote today. This is achieved by signalling the existence of equally imaginary group norms.41

Ample evidence of this phenomenon can be found by simply Googling “The Climbing Community”. Article after article can be found where the author asserts ‘The Climbing Community thinks X’ or ‘The Climbing Community must do Y’. What this really means is “I think Z is good/bad and I want you to do so as well. I’m not going to say this explicitly though; instead, I’m going to use this imaginary entity to try and convince you that everyone like you already agrees with me”. The term is usually accompanied by use of first-person plural pronouns — we, our — instead of the second-person — you. This is a well-documented tactic of politicians seeking to evoke other imagined communities42 to mobilise those who identify with those ‘communities’43 by engendering feelings of familiarity44 and interdependency.45

Put more simply: The Climbing Community™ is a rhetorical device. Use of this device is unethical, no matter how good the journalist’s intentions are or how worthy the cause is they wish to advocate for is. This is because its usage aims to manipulate readers’ ideas, not only about what to think, but also about what a community actually is, about what entities exist in the world, and, more sinisterly, about who they are as a person. Consequently, the term may dissuade atomised people from seeking out real communities which means that they miss out on the huge well-being benefits associated with them.46

So to deconstruct the rhetorical effects, next time you see this term simply replace it with the more honest term “people who go climbing”, swap the first-person plural for the second-person, and observe as everything suddenly feels as if it is being written in the imperative.

The dishonesty of this term is instantly recognised by anyone who belongs to a real community, such as a village, a church, or a climbing club. They know first-hand what a community really consists of and so see straight through the language. But alas in our modern atomised world increasingly few people belong to such real communities, and unfortunately many people desperately, instinctively, and unreflectively (though understandably) cling to the illusory journalist-created imagined communities that are pushed upon them.

The fourth purpose of The Climbing Community™ is to allow business owners to associate their products with it. The hope is that identified/fused individuals also incorporate the consumption of those products into their sense of self.47

The most brazen example of a firm using this tactic is the energy drink company Tenzing48, which strategically built its entire brand around the idea that people who climb are a unified entity which could then be influenced into becoming the brand's loyal ‘tribe’. This would not be a viable strategy if (a) we did not live in an atomised society or (b) this imagined community had not already been installed in the heads of so many people.

Real Climbing Communities

So what do real climbing communities look like? Obvious examples are organised climbing clubs, scenes at specific walls or crags, competition squads, groups of mates who meet up and climb together, climbing couples49 and partnerships,50 even an ultra-casual group-chat is far more of real community than The Climbing Community™. Climbing festivals or competitions can constitute temporary communities which can open doors to more permanent forms of community.51 Also worthy of mention are climbing-related task groups such as mountain rescue teams, guidebook committees, access teams, outreach organisations, bolt funds and so on.

All of these things are real. The Climbing Community™ is imaginary.

Conclusion

If you identify with The Climbing Community™, here are some concrete steps you can take to engage with real communities and enhance your well-being. Find and participate in the local outdoor scene, join a club, volunteer with an organisation, offer to take novices outside, or join an organised group down at the local climbing wall. Forge partnerships with people instead of seeing your belayers as mere ‘rope holders’. Try to make friends with the people you meet while climbing — even simple conversations with strangers can lead to significant well-being benefits.52 You could even consider founding your own community; it could be as straightforward as a group chat for people you regularly see down the crag or wall, or as unusual as a Discord community for discussing niche areas of climbing. By intentionally re-establishing and maintaining a world of ‘little platoons’ or ‘neo-tribes’ we move towards a world where we are no longer atomised, people are happier, more resilient, and better able to flourish.

So do your part by pointing out the dishonesty of The Climbing Community™ tactic when you see it being used. You may also wish to make a concerted effort to defuse from and deidentify with The Climbing Community™. This can be done by identifying as a person-who-climbs rather than as a member of this imaginary community. At the end of the day though, there isn’t much wrong with believing you’re in an imaginary group as long as you are aware that is what you are doing. But if you do, don’t let journalists or brands determine what you think, what you buy, or who you are. Your real communities can do that.53

Punter, T. (2023). There’s No Such Thing as the Climbing Community. In Diary of a Punter.

Rickly, J. M. (2017). “I’m a Red River local”: Rock climbing mobilities and community hospitalities. In Tourist Studies.

Climber, M. (2023). UFCK Magazine: Issue 8.

See also: Halbert, D. From Route Finding to Redpointing: Climbing Culture as a Gift Economy. (2010). In Climbing - Philosophy for Everyone.

Cooley, E., Payne, B. K., Cipolli, W., Cameron, C. D., Berger, A., & Gray, K. (2017). The paradox of group mind: “People in a group” have more mind than “a group of people”. In Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

von Ehrenfels, C. (1890/1988). On 'Gestalt Qualities'. (B. Smith, Trans.). In Foundations of Gestalt Theory.

In the case of all things that have several parts and in which the whole is not like a heap, but is a particular something besides the parts, there must be some such uniting factor.

Aristotle. (1960). Metaphysics. (R. Hope, Trans.). University of Michigan Press.

This is the case for other species too. Baboons understand social entities as existing over and above the individual members that compose it at any one time.

Seyfarth, R. M., & Cheney, D. L. (2017). Precursors to language: Social cognition and pragmatic inference in primates. In Psychonomic Bulletin & Review.

Moffett, M. W. (2018). The Human Swarm: How Our Societies Arise, Thrive and Fall. Head of Zeus. Chapter 6.

Lickel, B., Hamilton, D. L., Wieczorkowska, G., Lewis, A., Sherman, S. J., & Uhles, A. N. (2000). Varieties of groups and the perception of group entitativity. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Sherman, S. J., Castelli, L., & Hamilton, D. L. (2002). The spontaneous use of a group typology as an organizing principle in memory. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Plötner, M., Over, H., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2016). What Is a Group? Young Children’s Perceptions of Different Types of Groups and Group Entitativity. In PLOS ONE.

Lickel, B., Rutchick, A. M., Hamilton, D. L., & Sherman, S. J. (2006). Intuitive theories of group types and relational principles. In Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Moffett, M. W. (2013). Human Identity and the Evolution of Societies. In Human Nature.

Nonetheless, social categories are percieved as more entitative than a collection of random people. Even the category ‘people who are single’ is judged as more entitative than a random set.

Fisher, A. N., & Sakaluk, J. K. (2020). Are single people a stigmatized ‘group’? Evidence from examinations of social identity, entitativity, and perceived responsibility. In Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Plötner et al (2016).

Campbell, D. T. (1958). Common fate, similarity, and other indices of the status of aggregates of persons as social entities. In Behavioral Science.

See also: von Ehrenfels, C. (1914/1988). Gestalt Level and Gestalt Purity. (B. Smith, Trans.). In Foundations of Gestalt Theory.

Steinhart, T., & Gierl, H. (2017). Who Would Like to be Treated Fairly? Utilizing the Entitativity and the Singularity Concept for Creating Effective Advertisements to Promote Fair-Trade Products. In Marketing ZFP.

Data taken from Lickel et al (2000).

Górska, E. (2003). On partonomy and taxonomy. In Studia Anglica Posnaniensia.

Lickel et al (2000); Sherman et al (2002); Plötner et al (2016).

For example: Vestner, T., Tipper, S. P., Hartley, T., Over, H., & Rueschemeyer, S.-A. (2019). Bound together: Social binding leads to faster processing, spatial distortion, and enhanced memory of interacting partners. In Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

Rossignac-Milon, M., Bolger, N., Zee, K. S., Boothby, E. J., & Higgins, E. T. (2021). Merged minds: Generalized shared reality in dyadic relationships. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Entitativity scores differ for chosen social categories and unchosen social categories. Entitativity ratings also differ between categories of a similar nature: for example, Jews, Muslims and Hindus are judged to be far more entitative categories than atheists or ‘the spiritual’.

Demoulin, S., Leyens, J.-P., & Yzerbyt, V. (2006). Lay Theories of Essentialism. In Group Processes & Intergroup Relations.

Toosi, N. R., & Ambady, N. (2011). Ratings of Essentialism for Eight Religious Identities. In International Journal for the Psychology of Religion.

Johnson, A. L., Crawford, M. T., Sherman, S. J., Rutchick, A. M., Hamilton, D. L., Ferreira, M. B., & Petrocelli, J. V. (2006). A functional perspective on group memberships: Differential need fulfillment in a group typology. In Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Martela, F., Lehmus-Sun, A., Parker, P. D., Pessi, A. B., & Ryan, R. M. (2023). Needs and Well-Being Across Europe: Basic Psychological Needs Are Closely Connected With Well-Being, Meaning, and Symptoms of Depression in 27 European Countries. In Social Psychological and Personality Science.

Cavazza, N., Pagliaro, S., & Guidetti, M. (2014). Antecedents of Concern for Personal Reputation: The Role of Group Entitativity and Fear of Social Exclusion. In Basic and Applied Social Psychology.

Dang, J., & Liu, L. (2020). When peer norms work? Coherent groups facilitate normative influences on cyber aggression. In Aggressive Behavior.

Baron, R. S. (2005). So Right It’s Wrong: Groupthink and the Ubiquitous Nature of Polarized Group Decision Making. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology.

Waytz, A., & Young, L. (2012). The Group-Member Mind Trade-Off. In Psychological Science.

Marques, J., Abrams, D., & Serôdio, R. G. (2001). Being better by being right: Subjective group dynamics and derogation of in-group deviants when generic norms are undermined. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Abrams D., Marques J. M., de Moura G. R., Hutchison P., Bown N. J. (2004). The Maintenance of Entitativity. In The Psychology of Group Perception.

Lewis, A. C., & Sherman, S. J. (2010). Perceived Entitativity and the Black-Sheep Effect: When Will We Denigrate Negative Ingroup Members? In The Journal of Social Psychology.

Hogg, M. A., Sherman, D. K., Dierselhuis, J., Maitner, A. T., & Moffitt, G. (2007). Uncertainty, entitativity, and group identification. In Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Callahan, S. P., & Ledgerwood, A. (2016). On the psychological function of flags and logos: Group identity symbols increase perceived entitativity. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Butz, D. A. (2009). National Symbols as Agents of Psychological and Social Change. In Political Psychology.

In other words, social identification comes packaged with is-ought violations.

Sundararajan, L., & Yeh, K.-H. (2021). Strong Ties and Weak Ties Rationality: Theory and Scale Development. In Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science.

Schmidt, M. F. H., Rakoczy, H., & Tomasello, M. (2012). Young children enforce social norms selectively depending on the violator’s group affiliation. In Cognition.

Roberts, S. O., Gelman, S. A., & Ho, A. K. (2017). So It Is, So It Shall Be: Group Regularities License Children’s Prescriptive Judgments. In Cognitive Science.

Liberman, Z., Howard, L. H., Vasquez, N. M., & Woodward, A. L. (2018). Children’s expectations about conventional and moral behaviors of ingroup and outgroup members. In Journal of Experimental Child Psychology.

Marques, J. M., Yzerbyt, V. Y., & Leyens, J.-P. (1988). The “Black Sheep Effect”: Extremity of judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification. In European Journal of Social Psychology.

Reiman, A.-K., & Killoran, T. C. (2023). When group members dissent: A direct comparison of the black sheep and intergroup sensitivity effects. In Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Hales, A. H., Ren, D., & Williams, K. D. (2016). Protect, Correct, and Eject: Ostracism as a Social Influence Tool. In The Oxford Handbook of Social Influence.

Swann, W. B., Gómez, Á., Seyle, D. C., Morales, J. F., & Huici, C. (2009). Identity fusion: The interplay of personal and social identities in extreme group behavior. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

See also: Aron, A., Lewandowski, G., Branand, B., Mashek, D., & Aron, E. (2022). Self-expansion motivation and inclusion of others in self: An updated review. In Journal of Social and Personal Relationships.

For the moral and political implications of this see:

Sandel, M. (1998). Liberalism and the Limits of Justice. Cambridge University Press.

Lobato, R. M., & Sainz, M. (2021). Collective Rituals in Times of the COVID-19 Quarantine: The Relationship between Collective Applause and Identity Fusion. In Studia Psychologica.

Pretus, C., & Vilarroya, Ó. (2022). Social norms (not threat) mediate willingness to sacrifice in individuals fused with the nation: Insights from the COVID‐19 pandemic. In European Journal of Social Psychology.

Buhrmester, M. D., Newson, M., Vázquez, A., Hattori, W. T., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Winning at any cost: Identity fusion, group essence, and maximizing ingroup advantage. In Self and Identity.

Purzycki, B. G., & Lang, M. (2019). Identity fusion, outgroup relations, and sacrifice: A cross-cultural test. In Cognition.

Paredes, B., Briñol, P., Petty, R. E., & Gómez, Á. (2021). Increasing the predictive validity of identity fusion in leading to sacrifice by considering the extremity of the situation. In European Journal of Social Psychology.

Fredman, L. A., Bastian, B., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2017). God or Country? Fusion With Judaism Predicts Desire for Retaliation Following Palestinian Stabbing Intifada. In Social Psychological and Personality Science.

Chinchilla, J., Vazquez, A., & Gómez, Á. (2021). Identity fusion predicts violent pro-group behavior when it is morally justifiable. In The Journal of Social Psychology.

Wibisono, S., Louis, W. R., & Jetten, J. (2022). Willingness to Engage in Religious Collective Action: The Role of Group Identification and Identity Fusion. In Studies in Conflict & Terrorism.

Talaifar, S., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2019). Deep Alignment with Country Shrinks the Moral Gap Between Conservatives and Liberals. In Political Psychology.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Brashears, M. E. (2006). Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades. In American Sociological Review.

Thulin, E., & Vilhelmson, B. (2019). More at home, more alone? Youth, digital media and the everyday use of time and space. In Geoforum.

Kashima, Y., Kashima, E., Chiu, C.-Y., Farsides, T., Gelfand, M., Hong, Y.-Y., Kim, U., Strack, F., Werth, L., Yuki, M., & Yzerbyt, V. (2005). Culture, essentialism, and agency: are individuals universally believed to be more real entities than groups? In European Journal of Social Psychology.

Spencer-Rodgers, J., Williams, M. J., Hamilton, D. L., Peng, K., & Wang, L. (2007). Culture and group perception: Dispositional and stereotypic inferences about novel and national groups. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Tsukamoto, S., Kashima, Y., Haslam, N., Holland, E., & Karasawa, M. (2018). Entitativity Perceptions of Individuals and Groups across Cultures. In The Psychological and Cultural Foundations of East Asian Cognition: Contradiction, Change, and Holism.

Chiu, L.-H. (1972). A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Cognitive Styles in Chinese and American Children. In International Journal of Psychology.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. In Psychological Review.

Yuki, M. (2003). Intergroup Comparison versus Intragroup Relationships: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Social Identity Theory in North American and East Asian Cultural Contexts. In Social Psychology Quarterly.

Kurebayashi, K., Hoffman, L., Ryan, C. S., & Murayama, A. (2010). Japanese and American Perceptions of Group Entitativity and Autonomy. In Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology.

Reeskens, T., & Wright, M. (2012). Nationalism and the Cohesive Society: A Multilevel Analysis of the Interplay Among Diversity, National Identity, and Social Capital Across 27 European Societies. In Comparative Political Studies.

Shi, C.-C. (2018). Defining My Own Oppression: Neoliberalism and the Demands of Victimhood. In Historical Materialism.

Xu, Y., Burns, M., Wen, F., Thor, E. D., Zuo, B., Coley, J. D., & Rhodes, M. (2022). How Culture Shapes Social Categorization and Inductive Reasoning:A Developmental Comparison between the United States and China. In Journal of Cognition and Development.

Kalman-Lamb, N. (2020). Imagined Communities of Fandom: Sport, Spectatorship, Meaning and Alienation in Late Capitalism. In Sport in Society.

Charles Taylor has argued that it is more appropriate to classify nations as something like a task group where the shared task is the building and conservation of the nation upon which all citizens’ security and fate ultimately depends. The ‘community’ is still imaginary — i.e., not a real community based on intimacy and personal relation — but is definitely more entitative/group-like than a mere category. This line of argument is more fertile ground for those who still want to reify ‘people who go climbing’ into a group. Defenders of such a position would need to contend that ‘people who go climbing’ exist in the same way The English exist — thus ‘The Climbing Nation’ seems a more appropriate description of such an entity. Even so, it isn’t clear how speed climbers from Iran, boulderers from Papua New Guinea, and ice climbers from the Netherlands could reasonably be identified as sharing a task or a fate.

Taylor, C. (2003). Cross-Purposes: The Liberal–Communitarian Debate. In Debates in Contemporary Political Philosophy.

Malka, A., Soto, C. J., Inzlicht, M., & Lelkes, Y. (2014). Do needs for security and certainty predict cultural and economic conservatism? A cross-national analysis. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Khalil, E. L. (2018). Does identity fusion give rise to the group – or the reverse? Politics- versus community-based groups. In Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

Jutzi, C. A., Willardt, R., Schmid, P. C., & Jonas, E. (2020). Between Conspiracy Beliefs, Ingroup Bias, and System Justification: How People Use Defense Strategies to Cope With the Threat of COVID-19. In Frontiers in Psychology.

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

Ellul, J. (1973). Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes (K. Kellen and J. Lerner, Trans.). Random House. Pages 91—3.

Anderson also proposed that these made-up identities are artificial products of modernity and mass media, and this is where he and I diverge. Our shared imaginings bind people together with a mental force no less valid and real than the physical force that binds atoms to molecules, turning them both into concrete realities. This has been the case for all time.

Moffett, M. W. (2018). The Human Swarm: How Our Societies Arise, Thrive and Fall. Head of Zeus. Page 18.

Theory also becomes a material force as soon as it has gripped the masses.

Marx, K. (1844). A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right.

This is what Ellul calls sociological propaganda: artificial social entities are asserted to exist which individuals’ attitudes are then sculpted around. Pages 63—70.

It is no coincidence that the surge in usage of The Climbing Community™ coincided with the megathreat of COVID-19. Experience of threats leads people to seek out entitative groups to bind to for security. And when you’re locked alone in your house, legally prohibited from interacting with anyone, all you really have are your categories.

Of course we must acknowledge, as Sir Roger Scruton put it, that “the consolation of imaginary things is not imaginary consolation”. However, from Johnson et al (2009) we know that categories and real communities do not provide the same amount or type of consolation. Thus the opportunity costs resulting from mistaking categories for communities are potentially significant.

Castano, E., Yzerbyt, V., Paladino, M.-P., & Sacchi, S. (2002). I Belong, therefore, I Exist: Ingroup Identification, Ingroup Entitativity, and Ingroup Bias. In Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Jutzi, C. A., Willardt, R., Schmid, P. C., & Jonas, E. (2020). Between Conspiracy Beliefs, Ingroup Bias, and System Justification: How People Use Defense Strategies to Cope With the Threat of COVID-19. In Frontiers in Psychology.

Gelfand, M. J. (2021). Cultural Evolutionary Mismatches in Response to Collective Threat. In Current Directions in Psychological Science.

Lobato, R. M., & Sainz, M. (2021). Collective Rituals in Times of the COVID-19 Quarantine: The Relationship between Collective Applause and Identity Fusion. In Studia Psychologica.

Scruton, R. (2006). Modern Culture. Continuum. Page 18.

Ellul distinguishes between agitation propaganda — which aims to mobilise the group against the journalist’s opponents — and integration propaganda — which aims to unify and stabilize the group by getting the members to share the stereotypes, beliefs and reactions of the group. Page 70—9.

Most uses of The Climbing Community™ are instances of integration propaganda, though recently instances of agitation propaganda using this term have been directed at athletes from certain countries, and against business owners who are disapproved of.

The best counterargument to pointing out that The Climbing Community™ is imaginary is that resultant loss of belief in this entity could result in increased violation of norms against chipping, against antisocial behaviour and other norms buttressing appropriate standards of behaviour. An anonymous reviewer pointed out that norm transmission and enforcement was particularly necessary in the context of a world where climbers are not initiated into the old ways by a mentor and therefore have fewer means to learn what good ethical practices are. I would respond by saying that ethical behaviours do not require this entity to exist in order to be legitimate, but would have to admit that The Climbing Community™ probably does increase compliance somewhat given the atomised ecology we live in. However, this benefit isn’t worth deluding yourself or anyone else over the true nature of The Climbing Community™ — this is unethical in its own way. Regardless, some may still argue the collective benefits outweigh the individual costs; thus claiming that The Climbing Community™ is a noble lie.

Proctor, K., & Su, L. I.-W. (2011). The 1st person plural in political discourse—American politicians in interviews and in a debate. In Journal of Pragmatics.

Yin, Y., Wakslak, C. J., & Joshi, P. D. (2022). “I” am more concrete than “we”: Linguistic abstraction and first-person pronoun usage. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Steffens, N. K., & Haslam, S. A. (2013). Power through ‘Us’: Leaders’ Use of We-Referencing Language Predicts Election Victory. In PLoS ONE.

Adam-Troian, J., Bonetto, E., & Arciszewski, T. (2021). “We Shall Overcome”: First-Person Plural Pronouns From Search Volume Data Predict Protest Mobilization Across the United States. In Social Psychological and Personality Science.

Orvell, A., Gelman, S. A., & Kross, E. (2022). What “you” and “we” say about me: How small shifts in language reveal and empower fundamental shifts in perspective. In Social and Personality Psychology Compass.

Fitzsimons, G. M., & Kay, A. C. (2004). Language and Interpersonal Cognition: Causal Effects of Variations in Pronoun Usage on Perceptions of Closeness. In Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Housley, M. K., Claypool, H. M., Garcia-Marques, T., & Mackie, D. M. (2010). “We” are familiar but “It” is not: Ingroup pronouns trigger feelings of familiarity. In Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Na, J., & Choi, I. (2009). Culture and First-Person Pronouns. In Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Xue, X., Reed, W. R., & Menclova, A. (2020). Social capital and health: a meta-analysis. In Journal of Health Economics.

Lim, C., & Putnam, R. D. (2010). Religion, Social Networks, and Life Satisfaction. In American Sociological Review.

VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). Religious Communities and Human Flourishing. In Current Directions in Psychological Science.

Samtani, S., Mahalingam, G., … Brodaty, H. (2022). Associations between social connections and cognition: a global collaborative individual participant data meta-analysis. In The Lancet Healthy Longevity.

Krishna, A., & Kim, S. (2021). Exploring the dynamics between brand investment, customer investment, brand identification, and brand identity fusion. In Journal of Business Research.

See also: Grey, S., & Newman, L. (2018). Beyond culinary colonialism: indigenous food sovereignty, liberal multiculturalism, and the control of gastronomic capital. In Agriculture and Human Values.

Cropley, C. J. (2004). The Effect of Couple Entitativity on Attributions, Nonverbal Communication, and Relational Satisfaction. University of Santa Barabara. PhD Thesis.

Walsh, C. M., & Neff, L. A. (2018). We’re better when we blend: The benefits of couple identity fusion. In Self and Identity.

Xu, Q. (2019). Entitativity in Romantic Couples: What It Means, How Partners Report It, and Its Implications. New York University. PhD Thesis.

It is well known that climbing partnerships can have an identity of their own, over and above that of the individuals involved. Popular British examples of this might be Brown and Whillans, Ben and Jerry, and the Wideboyz.

Fine, G. A., & van den Scott, L.-J. (2011). Wispy Communities: Transient Gatherings and Imagined Micro-Communities. In American Behavioral Scientist.

Páez, D., & Rimé, B. (2014). Collective emotional gatherings. In Collective Emotions.

Folk, D., & Dunn, E. (2023). A systematic review of the strength of evidence for the most commonly recommended happiness strategies in mainstream media. In Nature Human Behaviour.

I am grateful to Dr Kimborough Moore, Modern Climber, Chris Shawarma, Esq., and several anonymous reviewers who kindly provided comments on drafts of this article. Special thanks to Dr Paul Sagar for his article on this topic.

Thanks for writing this - it's a relevant discussion to current societal trends. With respect to numerous other groups ( sports, religious or even pub gatherings ) you have provided evidence of weakening cohesion. These trends have been ongoing for some decades but took a boost from pandemic politics - which further atomised and shattered public solidarity with devastating strikes on liberty of speech, behaviour and movement.

While mistrust for social gathering was boosted, attention was focused inwards - into our homes, computers and screens, to replace human contact and interaction with doom scrolling. The public now more than ever looks to the digital interface for information, comfort, and authority. The opportunities for technocratic rule and manipulation are rife.

Damage done in the climbing world is just a swish of the dragons tail, unrecognised by many. Your writing is a worthy exposé of these trends, important as they are to our group needs for interaction. Perhaps further evidence lies in the rising (?) interest in solo climbing (rope-solo) which I have been following for a couple of years. I even bought some new kit (sucker !) but got to a sticking point - how would my sporting interest look and feel without human companionship and interaction ?

Awareness is an important and essential 1st step. Bravo !

I feel the slow death of online forums and the speedy rise of short form social media helped along atomisation. I miss the forum days.