Forgetting to Experience: Technology and the Transmogrification of Climbing

How the romantic spirit of climbing was crushed under the boot of technology. Or, how rock climbing became a video game.

In a recent article John Porter argued that Climbing Has Succumbed To Numbers. Porter observes that climbing seems to no longer be about the embodied experiences that it gives you, and has instead become a means to acquiring grades, ticks, records and so on. For many these abstract representations of the climbing experience are now considered the end-goal of climbing:1

Commercialism in mountaineering has taken a spiritually transcendental pastime, and flattened it into neutered commodities that can be sold as mountain tourism adventures. […] In this ‘fast-food’ fixation on commodification, consumerism and competition, something of the philosophy of climbing and mountaineering has also been lost. Peak bagging can become an end in itself, a joyless number-counting exercise — unless each moment is lived.

What Porter is articulating is the final destination of a trend that has been going on for a long time: a slow but definitive cultural movement away from emphasising the embodied climbing experience towards seeking ever greater efficiency and performance.2 Speaking in 1957, Geoffrey Winthrop Young, founder of the British Mountaineering Council, spoke fatalistically about this inevitable end-point of climbing:

The mountain influence, working in early ages subconsciously, then through conscious and artistic appreciation, and abruptly in this last century awakening to a passion for contact and achievement, is now progressing by our human law always towards technique and perfected method in climbing, and it can recapture always less of the first magical awareness of the inner mountain feeling.3

So here we are, living in a world where what was intuitive and obvious to the climbers of the past is not so to the new generations of climbers raised in the gym and guided by algorithmically delivered parasocial role models. For these people — especially those who were never initiated into the philosophy of climbing by a mentor — it simply isn’t apparent that climbing could ever have been about anything other than getting the big numbers, ticking the routes or getting the likes on social media. Indeed, some reading this may well be thinking: what other reasons could there possibly be?

Conversely, older generations surveying the current state of climbing find themselves looking around in total bewilderment and are unable to explain what has happened. How did we end up here? Where did the spirit of climbing go?

This essay will answer these questions. Here we will explore some of the mechanisms by which climbing was transformed from a romantic experiential practice into something closer to gymnastic accountancy. We will do this by referring to the writings of climbers and academics who over the past 120 years have observed, predicted and warned about this trend.4

We'll begin with discussing the romantic vision of climbing, and show how this traditional motivation was crowded-out and lost. Specifically, we will show how technologies that were intended to enhance the climbing experience inadvertently provided alternative goals. These new goals took climbers’ attention away from cultivating climbing experiences. In turn, these new goals were harnessed by commercialisation and relentlessly promoted until they became widely understood as the purpose of climbing. The romantic spirit of climbing was then finally extinguished when positive experiences became understood simply as technical means to meet these new goals.

Unadulterated Experience: Romantic Climbing 🏞️

Romantic climbers argue that the purpose of climbing is the embodied experience of the climbing.5 The whole point of the exercise is to be attentive towards the experience of the challenge of climbing the rock, to the beauty of the rock, its surroundings, and the movement and effort it demands.6 The rock is taken as it is found, it is accepted for what it is; desire to control the rock is let go and the climb is allowed to unfold naturally, rather than being coerced into shape according to one’s preconceptions (or literally via chisel, drill and hammer). The climber remains open to whatever the rock has to give, and enters with a resolve to maintain a constant uncritical attentive openness towards whatever sensations, emotions, feelings or meanings might be given. Charles Edward Matthews, writing in 1900, neatly articulated this attitude:

The mountaineer who loves nature for her own sake […] knows what a great mountain has to teach him, and he prepares himself to receive the lesson with a sympathetic and a reverent heart. He trains his body and keeps open his mind. Undue bodily fatigue is unknown to him, and therefore he always possesses the maximum capacity of appreciation. To him every tree, or fern, or flower has its tale to tell; to him the jagged rocks reveal their own history; to him the glory of the sunlight on the eternal snows, and the "silence that is in the starry sky" alike bring happiness and peace.7

The moment-to-moment experience yielded by Nature is what it is all about; getting to the top ultimately matters little and is considered merely a side-effect of the engagement. Demanding routes result in one kind of experience and easy routes another, but both are valued.8

The romantic approach to climbing is part of a wider tradition of contemplative leisure.9 In this tradition technology is selected intentionally, with the aim of enhancing or intensifying the experience, but without tilting the odds too far in your favour or disconnecting you from your in-the-moment experience. As Professor (and ‘godfather of bouldering’) John Gill argues:

What is especially appealing in climbing is not a separation from, but an intense realization of the climbing experience.10

Arno Ilgner’s The Rock Warrior’s Way (2003) labels the directing of attention towards what you are experiencing as being in the ‘The Witness Position’. Ilgner urges a constant direction of this attention towards the here-and-now of the climbing — to observe it but not to reflect on it — and to simply relish being there, listening to what the rock gives to you:11

Accept the journey [of climbing]. Be at peace in it. Watch it. When you can be at one with the difficulty and the chaos, then you transcend it. You simply walk your path, being observant, paying attention.12

Johnny Dawes has referred to this as “being there and knowing where there is”; others have called this state “thereness”.13 The nature of climbing is such that being at least somewhat present in the moment is necessary for success, and even indoor climbing brings about this state to some degree,14 though the effects of climbing on real rock are likely to be even stronger.15

Hayden Kennedy summarised the romantic view of climbing thusly:

The ultimate alpine climb would be a spectacular line up a virgin face, no one nearby, with a good partner – and there wouldn’t ever be a word uttered about it. Stripping away all desires except the pure experience of the climb, escaping all expectations and our own egos, these are the real achievements. We should all dream of this… maybe one day it will become a reality.16

So why do romantic climbers exalt the experience of climbing? They would all argue that it is intrinsically good, but research has also identified several manifestly valuable elements of the experience of rock climbing: flow states,17 harmony and rhythm,18 an enhanced sense of ‘realness’,19 sense of the sacred,20 altered states of consciousness, mystical and peak experiences,21 feelings of coming home,22 sense of meaning, purpose and authenticity,23 connection to Nature,24 joy, peace, beauty, the sublime, goodness and truth,25 belonging and fellowship,26 and insight and understanding.27 These experiences can be personally transformative28 and can be so profound that they have led some to hold up mountains as objects of worship,29 have inspired environmentalist political movements30 and are cited as evidence for the existence of God.31 Others have hypothesised that climbing experiences played key roles in the development of human thought32 and in the creation of the world’s major religions.33

A final aspect of choosing to aim your attention at the embodied rock climbing experience is that doing so is entirely antithetical to the logic of technological civilisation.34 Risking one’s life for a climbing experience is an act of spiritual defiance towards a world of maximisation, efficiency, rationality and abstraction.35 When approached in this way the rock becomes a place on the edge of everything, a place where one can truly be free.36 R. L. G. Irving, writing in 1957, explains this:

One of the great rewards of mountaineering has been that it took us right away from sophisticated life, from machines and men’s inventions into places where Nature, unchanged by human hands, invited us to forget habits and convention, the whole attitude to an industrial age and become, for a few hours, as far as we could, children of Nature.37

The romantic approach to climbing was dominant in Britain at the turn of the 20th century. Key books articulating this vision are The Romance of Mountaineering (1935) and The Spirit of the Hills (1937), explicitly written in response to the burgeoning technology-driven modern approach to climbing.38 But before the romantic turn there was another way of viewing climbing: as the worthy practical matter of getting on top of something.

Climbing as Task: A Job of Work to Be Done👷♂️

The original unromantic view of climbing is that it is a task which is completed when you successfully reach the top. An early example of this is artillery officer Antoine de Ville’s 1492 aid climb of Mont Aigulle after being ordered to do so by King Charles VIII of France.39 Don Whillans was also observed to have had this attitude towards climbing.40

This obvious alternate end goal of climbing is not brought into existence by technology: anyone can seek to climb a hill just to get to the top rather than for the experience the hill will yield.41 In the absence of any technology these are the two main options on offer.42

Why Do We Use Technology in Climbing? ⚙️

Both getting to the top and enhancing the experience provide rationale for developing climbing technology. Ropes and climbing shoes arguably serve both of these ends, as does technology that protects us from the particularly harsh aspects of the natural environment.43 However, some technologies have the potential to tip the odds far enough in the climbers favour so as to compromise the climbing experience.44 To take an extreme example, catching the train up to the top of Snowdon is a manifestly lower quality climbing experience than going up via Crib Goch.45 But technology doesn’t have to be as ridiculous as this to have a negative impact. Dave Hardy contends that even apparently benign technology — such as guidebooks, cutting edge equipment and scientific training methods — reduces the contrast between climbing and day-to-day life and thereby erects a barrier between the climber and the highest forms of climbing experience.46

Whether a particular piece of technology improves or worsens the experience of climbing is personal, and can be a matter of great debate.47 Even crampons were controversial when they were introduced to British mountaineering as some considered ‘cutting steps’ to be an essential aspect of the climbing experience. Here Galen Rowell summarises his opinion on experience enhancing, and compromising, technology:

Climbing with a few classic tools that become extensions of the body is quite conducive to the sought-after feeling; using a plethora of gadgets is not.48

However, making things too easy is only one means by which technology can interfere with the climbing experience. Some technological innovations bring with them the possibility of new non-experiential goals which take attention away from focussing wholly on the experience of climbing.49 To use John Gill’s terminology, the existence of these goals takes us from a focus on the “inner” aspects of climbing, to seeing climbing as a means to “outer” or non-experiential goals.50 The rock is then reinterpreted in terms of the goals brought about by the technology, as Professor Neil Postman observes:

To a man with a pencil, everything looks like a list. To a man with a camera, everything looks like an image. To a man with a computer, everything looks like data. And to a man with a grade sheet, everything looks like a number.51

Over the past 120 years the development of climbing technology has wrought a multiplication in the number of salient “outer” ends competing for climbers’ attention. These new goals entered the cultural space, and began to compete with the romantic vision for cultural prominence. Consequently, the intrinsic value of the embodied climbing experience has become lost beneath the extrinsic goals brought into existence by technology.52 E. R. Blanchet, writing in 1950, warned prophetically:

Formerly, the mountaineer often combined in his personality the poet and the visionary. To-day and still to-morrow the ironmonger enters into it. If technique has not killed courage, has it not often destroyed something else infinitely more precious? Can the ironmonger and the poet live harmoniously in the same body, or does the first tend to drive out the latter?53

Cutting-Edge Tools: Supremacy and Professionalism 🔩

The first technological developments to definitively tip the odds in the rock climber’s favour were pitons and karabiners.54 With the advent of these technologies the rock became something that a climber could manipulate to guarantee success, rather than experience as-is. Anthony Rawlinson discusses this shift in his 1968 essay entitled Parting of the Ways:

In ‘conventional’ climbing, the physical configuration of the mountain is a fixed element. The climber climbs by making the movements of his body a variable. His agility and skill is to adapt his body to the shape of the mountain. There is a limit to his capacity to adapt. When the shape of the mountain lies beyond that limit, he cannot climb it. In artificial climbing the mountain is no longer a fixed element; it too becomes a variable. The climber’s agility, his capacity to adapt, is still limited, but he uses his pitons to adapt the mountain so as to bring it within his own limitations. Since in principle there need be no limit to this process, anything becomes climbable.55

Changing the rock is clearly at odds with the romantic ethic of seeking to experience the rock as it is. Frank Smythe contended that altering the rock with technology is to miss the point and spoil the experience in a way not dissimilar to fishing with dynamite.56 Hans Dülfer, interpreting the philosophy of romantic57 soloist Paul Preuss, identified an inherent link between a climber’s goals and his preparedness to alter the rock:

The distinction between artificial and natural aids […] clearly differentiates as to whether one is, as leader, also using the link formed by the rope in order to get up the mountain or precisely because one is climbing the mountain.58

However, these technologies also opened up the possibility for new, non-experiential ends. Specifically, these tools allowed the possibility of an even more decisive move away from valuing and focussing on one’s experience. The aim could now be more than just getting to the top: it would be to get to the top with maximal technological efficiency. Climbers from Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany adopted these tools and sought to implement them to their maximal potential; at least some of them saw this as a means to demonstrate the rationality, validity and futuristicness of their country’s governing political ideology.59

Note the difference in how Emilio Comici interpreted his 1933 aided first ascent of the north face of Cima Grande, and how it was received by editor of the Alpine Journal Colonel E. L. Strutt.

Comici: By the same light that illuminates the value and tenacity of the Italians of Mussolini, we have opened the path to the north face of the Tre Cime di Lavaredo.60

Strutt: To any one who has viewed it, the great N. face of the peak is one of the most forbidding and impossibly smooth precipices in the Alps; it has now obtained, deservedly, the much polluted title of 'the most difficult ascent in the Dolomites.' Needless to say, conquest was only effected by the means employed by steeple-jacks when dealing with factory chimneys. 'The difficulties approach' [but are not stated, like so often in modern amateurs' accounts, as surpassing] 'the limits of human possibility.'

Remarkable as is the guides' feat, it is one of those achievements that serve merely to bring discredit on present-day 'mountaineering.' Moreover when, as -stated in 'D.A.Z.,' 800 ft. of ordinary rope (to which were added another 500 ft. on August 13), 500 ft. of light rope, at least 90 pitons and 50 Karabiner, were employed in the ascent, the expedition is reduced to the piteous level of a repulsive farce.61

Comici frames his technological ascent as indicative of exceptional human ingenuity inspired by political ideology, whereas Strutt contends the ascent is akin to a professional steeple-jack scaling an industrial chimney and therefore an example of engineering not of mountaineering. Here we see a decisive split between romanticism and modernism. Comici sees the rock as a means to an outer end, which can be freely manipulated to yield that end, and Strutt is condemning this move. Indeed, many members of the British Alpine Club, identified as “romantics and reactionaries” by historians, vigorously opposed this burgeoning modern approach to climbing.62 This opposition is well documented in the Alpine Journal and several books written during this period63 and his since been judged as “ahead of its time”.64

Comici’s motivation is comparable to that of Cesare Maestri, who in an act of “extreme steeple-jacking”65 used a petrol powered compressor drill to place ~400 bolts during his attempt on the vertical Southeast Face of Cerro Torre. Maestri is quoted: “Hope is the weapon of the weak, there is only the will to conquer”.66 It is likely a man with this attitude would consider *not* using such a drill to be indicative of weakness and irrationality. When combined with his desire to “humiliate” his critics and his goal to “use climbing as a way of imposing [his] personality”,67 it is hard not to reach the conclusion that his efficient utilitarian use of technology to get to ‘the top’ — despite the criticism it would surely generate — was a key part of demonstrating his perceived superiority over his critics.

More generally, failure to utilise GPS devices, knee pads, climbing shoes, portable fans (in-situ halfway up cliffs), 3D-printed replicas, beta videos, 3D-rendered topos of routes, the latest scientific evidence, or other cutting-edge climbing technology, may be seen by some as inefficient, unprofessional and indicative of amateurism and moral weakness.68 Similarly, many see the lack of grid bolts on Stanage Edge — or any other traditional crag — as the irrational result of the love of gratuitous risk, rather than the desire to experience the rock as it is given. This is a result of thinking about climbing in a calculative, rational, efficiency-maximising way that is completely at-odds with the romantic idea that the highest quality climbing experience might require intentionally limiting one's use of technology.69

A final consideration is that buying and using cutting edge technologies can simply become ends in themselves.70 For example, climbing an offwidth just to use the giant cam you’ve just bought.

The Symbols Arrive: Guidebook World 📖

A second technological change that introduced new ends were maps and guidebooks and the measurements, names and grades they contain. These things clearly have the potential to improve and intensify the climbing experience by (1) making it harder to get lost and (2) allowing the climber to select climbs of quality and of sufficiently stimulating, but not excessive, difficulty.71 However, too much information can also tip the odds in the climber’s favour, as Dr Ian Heywood explains:

Guidebooks contain enormous amounts of information, much of it in a codified, convention-governed form; with these descriptions the competent interpreter approaches the climb with a considerable amount of reliable, intersubjectively verified knowledge. Unpredictability is significantly reduced, while the climber's ability to objectify and control the climbing environment increases. Objectification, predictability and control are of course hallmarks of rationalization.72

And as Peter Bartlett explains, all this information compromises the experience of confronting the unknown:

One obviously needs a certain amount of information to get to one’s mountain […] Yet at the same time information is deeply alien, because it enables imagination to usurp the actual experiencing of the frontier.73

Once again, the romantics of the Alpine Club recognised all the way back in the 1930s that climbing guidebooks — and the numbers, names and grades they contained — had the potential to transform mountaineering from a practice about experiencing the rock, to a practice of using the rock as a means to a non-experiential end. Guidebooks contain maps (route names, heights, grades and topos) that represent the territory (the rock and the experience of climbing the rock). If one spends too long dealing with (and obsessing over) maps, there is a risk of confusing the map for the territory. Frank Smythe writing in 1941 recounts his encounter with one such person:

When approaching such crags for the first time it is good fun to eschew guide-books and make the first few climbs at least by the light of Nature. In doing this the climber experiences the joys of pioneering and exploration. […] We reached the top of the crag after an enjoyable scramble, and later meandered back to the Pen y Grwyd Hotel. There we met an expert. He asked us where we had been, and we described a trifle vaguely the route we had taken. He was horrified. “Why,” he said, “you’ve been up a bit of Route Two, some of The Avalanche, a portion of The Roof,” and so on and so on. “You haven’t done a climb at all.” He spoke like a bishop admonishing a curate for putting too free an interpretation on the passages from the Scriptures. We felt crushed and humiliated. For all our enjoyment, for all a splendid and exhilarating scramble, we hadn’t done a climb at all.74

This reification of the map can lead to the ‘ticks’ and ‘grades’ becoming the whole point of climbing; rather than names and grades being a method of navigating the rock, they become the reason for climbing the rock. The rock becomes a means to the tick, a means to creating and completing a list, a means to the grade, and a means of quantitatively indicating your superiority over rivals. The rock is no longer a thing to be contemplated and instead becomes a set of variables to be entered into calculations in order to yield the ‘highest score’ possible. The risk that one day climbing might become understood as a game was identified long ago.75 Writing in 1904, Geoffrey Winthrop Young — in an article entitled Modern Climbing: A Protest — decried the gamification of climbing:

The thought of these great mountain rifts and precipices, carefully graded to the human powers, waiting through the ages purposeless until the time and needs of the climber claimed them, lends them an ever recurring fascination and mystery. But to treat such gymnastics as in themselves the end of climbing, to regard our beautiful English hills as so many targets whose sole interest is the size of the score we can make on them, so many bicycle tracks for record-breaking, is to justly earn the reproach of Philistinism.76

If reification is particularly extreme, the rock can be surrogated such that in the eye of the modern climber it becomes the name and the grade it is given. The rock is where the climb lives, not the thing which you are supposed to want to climb up. Some people can become so obsessed with the symbolic representations of rock that it becomes hard for them to know what is actually real. As David Smart summarises:

The literal, folkloric and even strictly geological memories of mountains faded to the background of climbers’ consciousness. Little roman numerals appeared besides the lines drawn on illustrations of peaks in guidebook illustrations. The Alps became a matrix of numbers and lines.77

And if you’ve lost the rock, then you’ve likely also lost the idea that the experience of the rock is itself valuable. Grade-chasing, plateau-lamenting, and puerile-ticking are the tell-tale symptoms of this affliction. Once this stage has been reached it is difficult (but not impossible) to find one’s way back.

Photography and Re-Representing Experience 🖼️

The camera has long been a part of climbing. Indeed, Joe Benson chronicles the history of climbing photography back to the 19th century. Photographs (somewhat) authentically record and share inspirational experiences, and act as invaluable aids to recall and reflect upon past experiences. Nonetheless, the camera cannot fully, or even adequately capture the ‘thereness’, the ‘rawness’ and the ‘nowness’ — or the depth — of a climbing experience.78 Accordingly, Dr Margret Grebowicz contends that the true reward of climbing is “that thing in the climbing body that cannot be reduced to pithy explanations or consumed by hungry spectators”.79 This echoes the opinion of John Muir, who wrote during the 1870s:

See how willingly Nature poses herself upon photographers’ plates. No earthly chemicals are so sensitive as that of the human soul. All that is required is exposure, and purity of material.80

But, much like guidebooks, camera technology itself is not neutral or inert. It too has the capacity to redirect attention away from the climbing experience. Firstly, cameras take away from a focus on the first-person experience currently being delivered by the rock, by introducing and exaggerating concerns about how you are being perceived.81 Secondly, the possession of a camera changes the encounter with beauty; coming face to face with a stunning view, or finding oneself doing an outlandish move, doesn't prompt a reaction of releasement and a sinking into the experience. Instead, the climber’s immediate thought is to pull out his camera to capture a re-representation of the experience he is now failing to have.82 As Susan Sontag writes:

A photograph is not just the result of an encounter between an event and a photographer; picture-taking is an event in itself, and one with ever more peremptory rights-to interfere with, to invade, or to ignore whatever is going on. Our very sense of situation is now articulated by the camera's interventions.83

And more disturbingly, cameras also contain the possibility of bending the whole climbing experience according to the demands of the lens. Indeed, since the introduction of photography people have been exploiting the authenticity-conferring nature of the photograph — in comparison to say, a sketch or a painting — to inflate the nature of their exploits.

Camera-less climbers could also visit portrait studios in major climbing centres in order to have their own heroic souvenir portraits take. These highly stylized images — often replete with fake outcrops and colourfully painted backgrounds — were extremely popular. A few decades later the images were considered to be theatrical and absurd, yet today it is precisely because of their obvious artificiality that they may strike us as charming.84

Over time this attitude has affected climbing itself. Even back in 1998, Benson was concerned at the increasing acceptability of photographers and athletes deliberately generating moments in order to photograph them, rather than simply preserving those moments which occur naturally.85 Thus, the purpose of climbing the rock becomes making the photo, rather than the purpose of the photo being to record and convey the experiences of the climbers on the rock.

Ed Douglas notes that modern software has allowed the creation of photos of events that never actually happened. Indeed it is now common practice for photographers to edit-out top-ropes in pictures taken in post-ascent ‘going back for the photos’ sessions. Practices such as these finally and completely divorce the photograph from the lived climbing experience.86

Camera technology made professional climbing pictures and films possible, and there is no doubt these can be extremely inspirational and serve to motivate the audience into having their own experiences of the rock. And as Benson argues, the possibility of capturing some of the inherent romantic nature of climbing meant that commerce inevitably attempted to harness climbing for profit.87

Commercialisation and the Media Age 💰

The introduction of commercialism to climbing meant that professionalism, ticks, grades, photos and videos, that already served to signal status and success, could now be monetised via sponsorship. Again, this adds another reason not to focus on the experience of the rock, and instead use it as a prop to help sell yourself. Professional climbers, fixated on these more easily communicable and ‘eye-catching’ goals, end up constructing their media output around the shallow but easily digestible “outer” ends of climbing.88 Furthermore, professional climbing contracts are constructed so as to tie salaries directly to ‘big grades’. As such, commercialism makes it difficult for the viewer to tell if a professional climber is, underneath it all, climbing for romantic reasons.

Commercialism further obscures the value of the climbing experience by placing demands on professional climbers’ attention. Dr Margret Grebowicz and David Roberts argue that having any kind of audience necessarily corrupts the ‘thereness’ of even the most ardent romantic athletes because they have to divert at least some attention towards imagining how their sponsors, advertisers and the general public are going to perceive their climbing. The conscious creation of a communicable spectacle is always going to interfere, to some degree, with an athlete’s focus on his or her embodied climbing experiences.89 Roberts writes:

The life-giving impulse behind our climbing has always been escapist, anarchistic, “useless,” Terray’s phrase. And one of the most satisfying rewards of going off to climbing is the opportunity it affords to shuck off the postures and personae that one carries through the “civilised” world. On expeditions there always used to be an absolute distinction between “out” and “in.” […] Even on a half-day rock climb, one normally ignores the complicated world we call “out” and instead penetrates the mysteries of self-reliance. On the climb, all that should matter is oneself, one’s partner, the rock, and the weather. Climbing is not an act that can be carried on publicly without considerable compromise. […] The difference between private and public climbing is like the difference between the act of love and a pornographic film.90

Competition between athletes for the public’s attention and the concomitant money from sponsors means that athletes are constantly measuring their “outer” achievements against those of other athletes. Irving warned about the experience-compromising effects of such competition:

There grows in the mere performance of difficult feats a competitive spirit that checks spontaneous enjoyment. We cannot enjoy our mountain to the full if we are keeping an eye, and it may be a very jealous eye, on the doings of others.91

The influence these professional climbers have on new, young and otherwise impressionable climbers means that their own ostensive drive for ticks, grades, photos, videos and efficiency — and lack of focus on the raw experience — is imitated and, over time, has eventually come to pervade the culture of climbing. This is for two reasons: (1) because humans observe and imitate behaviours that other humans get rewarded for;92 and (2) human beings learn what to want by copying the desires of those they look up to.93 Ben Burgis explains:

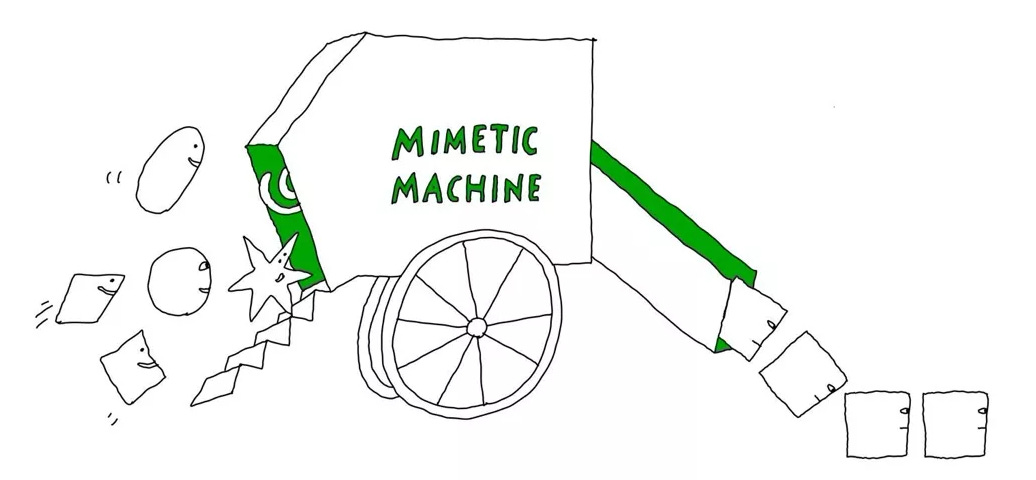

In the universe of desire there is no clear hierarchy. People don’t choose objects of desire the way they choose to wear a coat in the winter. Instead of internal biological signals, we have a different kind of external signal that motivates these choices: models. Models are people or things that show us what is worth wanting. It is models — not our “objective” analysis or central nervous system — that shape our desires. With these models, people engage in a secret and sophisticated form of imitation […] named mimesis.94

This process has been catalysed by the development of social media, which Burgis refers to as “the engines of desire”.95 Instead of being exposed to climbing role models once-in-a-while when an article or film was released, it became possible to have contact with them on a daily basis, even to the point of building one-way friendships with athletes.

Social Media: Everyone Turns Pro 🤳

The most charitable case for social media it that it allows you to share your passion for the experience of climbing, and to take inspiration from others to seek out experiences of your own. However, social media also serves to expand the pro-climber mindset — understanding climbing as a means to photos, ticks and grades etc. — to the general climbing public. This occurs for three reasons. Firstly, social media users are constantly exposed to pro climbers who are financially incentivised to climb and communicate “outer” goals. Second, pro-climbers are better able to forge parasocial relationships with their fans. Thirdly, social media allows the amateur climbers to more widely and concretely communicate their social status via the likes, views and followers they are able to yield using abstract representations of their own climbing experiences. All of these are exacerbated by algorithms which promote short, superficial and digestible representations of climbing: the boulder problem; the whip, the dyno, the big number, the green tick.96

What we commonly call “social media” is more than media — it’s mediation; thousands of people showing us what to want and coloring our perception of those things. […] Mimetic desire is the real engine of social media. Social media is social mediation — and it now brings [professional climbers] inside our personal world.97

Once amateurs start behaving like professional climbers then social norm effects kick in and pro-like social media activity starts cascading through climbing social media networks. Once this happens (1) not behaving like a professional climber is the weird thing and (2) your own “outer” ends become more valuable to you due to there being a greater number of others who consider “outer” ends to confer status. Why wouldn’t you climb for the ticks and grades you can post on social media? Why wouldn’t you constantly share how scientifically rational your training regime is? Why wouldn’t you dedicate huge quantities of your precious free time out of the city setting up tripods and flying drones? Indeed, how else will anyone know your climbing amounts to anything?

For the worst impacted climbers, the point of climbing a rock becomes being able to share a post on social media that you climbed the rock; the rock becomes a prop that increases the likes and views you get on your posts. Souvenirs become ‘content’; ethics like “if it’s not on Instagram then it didn’t happen” emerge and disappointment is felt when there is a failure to film ‘the send’. Now it is not just pros who begin to see the rock as the place which yields the spectacle. And thus, thanks to social media, it is not just professional athletes compromising the ‘thereness’ of their experiences by worrying about how their content will be perceived by their audience.

The pseudo-pro mindset is increasingly common; for many modern climbers the ultimate dream is not to have the ultimate climbing experience, but instead is to successfully make the transition from amateur to pro. Now even the most amateur climber finds himself dreaming of a Rock Technologies sponsorship, will proudly place a highly exclusive discount link from 3rd Rock in his Insta bio, tags multinational corporations in his Insta stories, and, for some reason, films and posts videos of his fingerboard sessions.

Above and beyond this, heavy users of climbing social media risk diminishing the novelty of their lived climbing experiences by reducing the contrast between their day-to-day lives and time where they are able to escape into Nature. If you’re watching climbing vids every day, actually being out there climbing is going to feel less novel and less special. Moreover, exposure to photos and videos of rock climbs prior to actually trying them yourself eliminates much of the joyful experiential process of adventure, of discovery and of solving it on your own. Chronic exposure to climbing videos can lead to a condition known informally as ‘beta vid burnout’ where the magic of climbing is no longer felt.

Romantics vs Modernists ⚔️

Here it is important to pause and note that the key difference between romantic climbing and modern climbing is ultimately not merely in the tools used, but in the motivations for climbing that the use of those tools make possible.98 A romantic climber is thus properly characterised by their belief that the embodied experience of climbing the rock is the end goal of climbing. In contrast, a modern climber is defined by their use of the rock as a means to some other, “outer”, non-experiential goal made possible by technology (the red boxes in the diagram). As such, it is possible — and indeed common — to meet romantic sport climbers, romantic boulderers, and modern trad climbers.99

The Gym: Sanitised Simulation of Reality 🎪

The final technological innovation we are to discuss, the climbing gym, while also creating a whole new set of alternative goals (e.g. being good at indoor climbing; winning indoor competitions), does not tend to take in-the-moment attention away from the rock climbing experience. After all, if you’re outside you’re likely far away from a climbing gym and it is unlikely to be intruding into your consciousness. However, the climbing gym’s effect is perhaps even more pernicious, and definitely more subtle, and has the potential to transform and blinker the rock climbing experience itself.

Why is this? Firstly, we must consider the things the gym has that the crag does not: music, huge quantities of people, the difficulty of routes unavoidably being presented on the holds, route-setter’s ‘intended beta’, the necessity of “getting your money’s worth”, time-limited routes, urgency due to closing time, numbered routes for ticking purposes, cafes, toilets, giant fans, and so on. Secondly, we have to consider the things the gym does not contain that are present in Nature: top-outs, unpredictable danger, hold-finding, weather conditions, hold conditions, sharp holds, ‘bad’ landings, long approaches, natural beauty, views, birds, plants, the sun, the stars and so on.

As you can see, in the climbing gym ‘inconvenience’ and ‘irrelevance’ is subtracted while convenience is added, in order to remove some of the ‘worst’ bits of the climbing experience while enhancing it with amenities. Thus a simulation of the outdoor reality is constructed, only with the sharp edges rounded smooth and much of the beautiful and precious context left out. Delaney Miller contends that some climbers will inevitably never step outside these Disneyland-like simulations:

Consider, for a moment, the social theorist Jean Baudrillard’s musings on the concept of simulacrum, which he defines as an evolution of the abstraction into its own reality so that the abstraction eventually becomes a distinct entity rather than a representation. It becomes original, or hyperreal, a stand in for the model itself. Indoor climbing is unmistakingly a simulacrum. Baudrillard went on to describe the inevitable “antecedence” of a simulacrum, such that the model eventually comes before its quintessential reality. At first, people went to climbing gyms to climb when the weather didn’t permit climbing outside. Later they went to gyms instead of going outside so that, when they did go back outside, they’d be stronger. But as climbing evolved, gyms became an end unto themselves; people began using gyms instead of venturing outside. Many never will.100

However, even those who do eventually step outside of the gym can inadvertently carry their indoor-derived attitudes and expectations out to the crag with them. As Miller notes, path dependency is at play. According to one’s path, the climbing wall is either seen as an imperfect way of bringing about the outdoor climbing experience, or the outdoors is seen as an imperfect way of bringing about the indoor climbing experience.101 Consequently, key aspects of the rock climbing experience aren’t savoured or recognised by indoor climbers as inherent parts of climbing, but instead are seen as inconvenient or uncomfortable things in the way of having a purely pleasurable time.102 Commensurate with this, the gym simulation itself has transformed, becoming ever less rock-like over time, reflecting users’ preference for holds and moves that are ‘fun’ or ‘accessible’ or ‘look good on Instagram’. Thus the gym simulation becomes ever more unlike rock, and more and more like an object of popular human desire.

Many indoor climbers who step into Nature conclude that experiencing its inconveniences is manifestly undesirable and so the rock ought to be transformed into being more like what they want. Some will be upset that the cosmic route-setter’s accidents of geology have not yielded the perfect consumption experience. Some of these will believe that simply taking what is given by Nature is manifestly irrational. As such, real rock that is encountered is then reinterpreted given their indoor-derived preferences, and found to be lacking.103 Holds are chipped to yield ‘better’ moves, holds are ‘comfortised’, landings are landscaped, all in order that the demands of the rock not yield anything but pleasure. Instead of a big spiky boulder in the landing being understood as part of the inherent challenge delivered by Nature, it is instead winched or rocked out of the way so as to deliver a more indoor-like experience for the climber. The convenience-maximising climber also demands bolts be added everywhere; indeed, why not bolt the Old Man of Hoy? It thus becomes increasingly difficult to find and experience rock that hasn’t been tampered with at some point — or as Johnny Dawes puts it, “doesn’t have bullshit painted all over it”.104 Why listen to Nature when everywhere it has visibly been broken and bent according to human desires?

Belief in the unimportance and total malleability of the outdoor context which surrounds ‘the climbs’ is perhaps not surprising. The context in which indoor routes sit in is there to be ignored as far as is possible. In the climbing gym, contemplative and meditative thinking is not encouraged, and is instead actively discouraged by a context of utilitarian aesthetics, crowds of people, and astoundingly banal music. Upon arrival, novices are immediately presented with the grading scale, and told to get to work. Calculative thinking is thus the default mindset of the climbing gym, and this too tags along and escapes into the outdoors. The portable Makita fan is the ultimate symbol of this: the din of the droning motor drowning out the silence and natural soundscape is judged a small price to pay — if considered at all — for a marginally improved chance at meeting an “outer” goal.

For many indoor climbers who venture outside, even if their goal isn't the tick or the grade, the rock is interpreted as the place ‘where the holds are’, not the thing which the whole enterprise of climbing is about experiencing. The aim of a day out is ‘do’ or ‘get’ the climbs, rather than experience the rock. This is mostly because the indoor climber simply expects the rock to yield an experience similar to that had by climbing a ‘Depot Red’. And, as we have discussed previously, what you expect partly determines what you will perceive. As such, the “inner” experience of the rock is anticipated, seen and interpreted through the lens of the “inner” experiences had in the climbing gym.

In the simulated Disneyland of the climbing gym it would seem utterly absurd to be wholly focussed on the holistic embodied experience of climbing the pink one in the corner. And if the climbing gym is the world you know, how would you know you ought to be focussing on what Crescent Arête, Stanage Edge, and the Peak District are giving to you?

Summary: The Modern Predicament 🌐

So let us put all these things together in a single diagram. As we can see, the original romantic meaning of climbing is still there, but it is increasingly hard to discover, lost amid a plethora of alternative “outer” goals made possible by technology.

Several of these goals involve abstract representations of the experience of the rock, namely: logbook ticks, grades, photos and videos. When a person confuses these representations for reality they are said to be experiencing hyperreality.105 However, ending up in hyperreality can only occur if a person’s attention is sufficiently and consistently drawn away from the manifestly valuable embodied experience of climbing and towards these extrinsic non-experiential “outer” goals. So why might this be happening?

Efficiency, Attention and Cultural Dominance🦾

The climbing experience can be judged as “higher quality” but it does not make sense for an embodied experience to be made “more efficient”.106 However, it certainly does make sense for “outer” ends to be brought about more efficiently. The high demands of the maximally efficient pursuit of these ends only further serves to obstruct any focus on the experience of climbing. Thus each new “outer” goal takes us further out of contemplation-mode and into calculation-mode, a process Hardy contends is a key aspect of the “McDonaldization of rock climbing”.107 Optimal pursuit of these superficial goals dominates our attention, we find ourselves always doing calculations of one kind or another, and the idea of deepening our experiences is almost entirely absent. Writing in 1954, Professor Jacques Ellul predicted that technology would lead to this happening in all sports:

A familiar process is repeated: real play and enjoyment, contact with air and water, improvisation and spontaneity all disappear. These values are lost to the pursuit of efficiency, records, and strict rules. Training in sports makes of the individual an efficient piece of apparatus which is henceforth unacquainted with any thing but the harsh joy of exploiting his body and winning.108

Now entire industries are built around the more efficient meeting of “outer” ends. Businesses are incentivised to push these non-experiential goals on impressionable climbers, to convince them that they are what climbing is about,109 and then to sell them efficient tools and techniques for how to attain them. YouTube and Instagram are full of influencers, coaches and companies urging you to adopt “outer” goals then sell you the most efficient ‘solution’ to ‘get’ them. See the video below for a textbook example of this:

The money these businesses generate allows them to dominate social media algorithms, commission films focussed on “outer” goals, sponsor and promote athletes without the brains or will to challenge their practices, and even determine which athletes are the ‘best value’ so that other businesses will do the same. These industries employ large teams of people with the aim of constantly churning out content with the implicit or explicit message: “climbing is about outer goals; pay us to tell you how to efficiently meet your outer goals; only then will you be happy”. In contrast, little money can be made from recommending to others that they prioritise their embodied experience of climbing. This incentive structure has led to full-spectrum-dominance of climbing culture by outer-end-focussed climbing media.110

Enslaving the Flow: Climbing as Video Game 🎮

The most despair-inducing inversion of the values of climbing are instances where mindfulness and flow states, instead of being understood as key aspects of the whole purpose of climbing, are presented as efficient methods by which to climb harder grades.111 The point here is not that this claim is false — on the contrary, it is well established that flow states and inward attention correlate with high performance situations112 — the point is that these aspects of experience, insofar as they matter at all, are framed in terms of their capacity to efficiently get you to the top. Here, we can clearly see that the original romantic end of climbing has not just been totally subordinated, it has been reduced to simply being one technical method among others.

Again, Ellul predicted this happening:

In every conceivable way sport is an extension of the technical spirit. Its mechanisms reach into the individual’s innermost life, working a transformation of his body and its motions as a function of technique and not as a function of some traditional end foreign to technique, as, for example, harmony, joy, or the realization of a spiritual good. In sport, as elsewhere, nothing gratuitous is allowed to exist; everything must be useful and must come up to technical expectations.113

This shift is part of a pattern of businesses attempting to instrumentalise and monetise flow states, which Professor John Vervaeke contends is the mechanism upon which video game industry is based.

Look at the things that induce the flow state [such as] rock climbing. Rock climbing makes no sense. It’s like something from Greek mythology by which you punish a person. “You! Climb up that rock face. You’ll hurt yourself, you’ll scrape yourself, you’ll get tired and hungry, you might fall […]; and once you get to the top, come back down.” Why do people do it? They do it because it reliably puts them into the flow state. Now we’ve found a way to hijack that and get people addicted: video games. Every addiction comes off hijacking something that is highly adaptive.

Video games systematically induce flow states and tie them to the meeting of non-experiential goals. After sufficient conditioning, the gamer will continue to pursue the non-experiential goal even if the game is no longer yielding the desirable experiences that were initially associated with it.114 This process can lead to a state of “amotivation”: doing activities to “relieve the feeling of boredom but without any purpose, apathetic, mentally disengaged and with little sense of meaning”. Amotivation has been identified as a major risk factor for video game addiction,115 is associated with anxiety and depression,116 and has been identified as a cause of dropping out of sports117 and of education.118

Moreover, video game companies have discovered that if you can get gamers to focus enough on non-experiential goals, then you can introduce “pay-2-win” dynamics where gamers exchange money in order to more quickly meet these goals. This is despite the fact that pay-to-win dynamics have the potential to compromise the in-the-moment experience of playing the game.119

A similar logic is currently as work in rock climbing, which cultural commentators have termed “cash-4-grades”. By systematically presenting extrinsic “outer” goals such as grades, ticks and efficiency as the point of climbing, companies are able to harness the intrinsic goodness of the embodied experience of climbing — of which flow states are but one part — and enslave it so as to transform rock climbing into something akin to a video game.120 Once this has been achieved, inexperienced and uninitiated new players ensnared by gamification will simply think it is rational to buy access to the tools and optimal strategies (the meta) that these companies claim to have identified for meeting the goals they systematically draw consumers’ attention to.121

But, like the gamer, the climber risks becoming conditioned such that desire for ticks, grades and photos becomes uncoupled from the positive embodied experiences initially associated with them. Conditioned climbers will thus chase these things even if doing so stops yielding joy, flow, fellowship and so on, and even if doing so starts yielding negative experiences.122 Climbers whose minds have been conquered in this way may be at risk of amotivation,123 boredom and despair,124 and existential crises.125 But climbing capitalists need not care about the fates of these people so long as the money is continuously rolling in from fresh generations of climbers whose understanding of climbing is ready to be gamified then monetised.

And so, due to technology and commercialisation, the idea that at the beginning of the 20th century defined the practice of climbing has been utterly lost by 2024. A few fringe voices are all that remain, quietly pointing out that maybe, just maybe, the point of climbing is to experience the climbing.126

Lost Romantics 🌀

If you come to rock climbing via the hyperreality-inducing world of social media, commercial climbing, the gym, and guidebooks, then discovery of the intrinsic goodness of the rock climbing experience is going to be tricky. Even people predisposed to be romantics who come to rock climbing via hyperreality may never escape.

But escape is not impossible.

The hyperreal can be escaped by choosing to remain in deliberate ignorance of abstract representations of rock climbs prior to climbing them. Even occasional practice is enough to clearly bring the “outer-inner” distinction into focus. If you find you simply must have a number to think about then consider trying statistical judo. Another approach is to read and follow The Rock Warrior’s Way (2003), a guide for how to train oneself to effectively minimise the influence of these “outer” goals on the embodied climbing experience. Dr Francis Sanzaro’s book The Zen of Climbing (2023) applies Buddhist teachings about embodied experience to climbing; Paul Pritchard’s book The Mountain Path (2021) advocates a similar approach.127 Philosophically minded climbers should investigate what phenomenology128 and mysticism have to say about climbing.129 Reading about how academics have thought about the romanticism-modernism conflict in climbing is another way by which to pull yourself out,130 as is trying to understand what exactly Johnny Dawes is talking about.

The most important thing, however, is always carefully selecting the technology one uses, always making sure that its presence is heightening the embodied experience and not compromising it. As Dr Neil Lewis summarises:

By listening to the reverberations of our bodies' in-the-world we can begin to delineate a sparing and preserving of temporal and spatial experience that is not enframed by technology. We might begin to do this by following the lead of adventure climbers and impose limits — limits defined by certain embodied experiences — as to the degree of control and mastery we exert over our environments. […] [We can] forego some of the safeties and certainties of modernity, in order to experience a deeper and more enriched lifeworld where natural forces provide mutual support and encouragement to human fulfilment.131

The rediscovery of the intrinsic goodness of the climbing experience might feel akin to remembering what it felt like to go climbing for the very first time. In Zen Buddhism the state of being open, eager, and with a lack of preconceptions is known as the Beginner’s Mind; Zen practitioners are encouraged never to forget it, never to lose it. But if it is lost, this does not mean it cannot be recovered:

Even mountaineering can be corrupted by commercializing [it] and making [it] subject only to extrinsic rewards. But the serious possibility of discovering the intrinsic value of engrossment remains at the periphery of commercialization and perennially recreates the opportunity for individual knowing. Perhaps that is why we call it “re-creation”.132

In-between mercilessly satirising the British climbing scene, Modern Climber has hypothesised that romantics lost in modern climbing go on a journey: (1) they start out with the beginner’s mind, with no knowledge of “outer” goals other than getting to the top; (2) exposure to technology, commercialism and modern climbing culture erodes this state until a total focus on the “outer” ends of climbing is reached; (3) an eventual recognition of the shallowness of a life lived in this way occurs; (4) a period of disenchantment/a “loss of psych” follows; (5) this yields to a period of attempting to work out what climbing is actually all about; (6) eventually a rediscovery of the romantic ideal is made; and (7) application of this leads to the possibility of a return of the beginner’s mind.133 He likens this to the following lines from T. S. Eliot’s Little Gidding (1942).134

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Once the embodied experience has been firmly placed back at the heart of your climbing, becoming a competent and strong cragsman makes even more sense. The better you are at climbing the more rock you will be able to safely interact with and experience. The set of intrinsically valuable things you can bear witness to will expand and expand. The fingerboard ceases to be “the efficient way to get 8A” and starts to be “the tool by which I will one day come to be able to experience rocks that have 8A attributed to them”. But to preserve this mindset technology must always be understood to potentially be experience-compromising, and it's inherent calculative ends need to be identified, charted and consciously steered clear of.135

Ultimately:

The price of freedom is eternal vigilance.136

Checking In With Reality 🪨

So with all that said, let us conclude with an exercise. Consider checking-in with your own relationship with the rock, your own relationship with Nature. You can do this by asking yourself the following questions:

Would I still climb if climbing grades didn't exist?

Would I still climb if topos didn’t exist?

Would I still climb if routes were not given names?

Would I still climb if I couldn't be photographed or filmed doing so?

Would I still climb if nobody else ever found out about my ascents?

Would I still climb if I only had access to suboptimal climbing technology?

Could I still value a climb if I deliberately stopped one move from the top?

If the answer to all of these is yes then you likely see the embodied experience of the rock as the point of climbing. If you answered no to any of the first five then you may well be trapped in hyperreality. Checking in with reality by asking yourself these questions is something worth doing regularly. You need to know you’re climbing for the right reasons:

Rare are the men who have so completely renounced the inner life as to hurl themselves gladly and without regret into a completely technicized mode of being. Such persons may exist, but it is probable that the “joyous robot” has not yet been born.137

Philip Bartlett expressed a similar sentiment in 2013.

Bartlett, P. (2013). Is Mountaineering a Sport? In Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement

Quite late on in writing this essay I discovered Dawn L. Hollis work on the history of the cultural understanding of mountains as a source of “gloom” to a source of “glory”. I suppose the present essay somewhat articulates the next phases of this development. A move from rock climbing being a source of experiential value (“glory: great beauty, or something special or extremely beautiful, that gives great pleasure”) to it being a source of external markers of success in the form of abstract representations of the climbing experience. This phase could be called Mountain Abstraction. The reinterpretation the positive aspects of the climbing experience — i.e. the ‘glory’ — in terms of its capacity to more efficiently yield these abstractions may represent us entering another phase: Mountain Nihilism.

Young, G. W. (1957). The Influence of Mountains Upon the Development of Human Intelligence: The seventeenth W. P. Ker memorial lecture delivered in the University of Glasgow, 2nd May, 1956. Jackson, Son & Company.

It is possible that some of us who in the old days marched out with uncertain steps to scale some untrodden peak, had a keener pleasure in victory than is known to this generation. Now the younger men are sometimes apt to question our authority and to underrate our achievements. I do not blame them. Authority is not good for much, unless it can stand the test of criticism and of time. But remember what is known to you, was unknown to us. We went out into a strange country, you—with a map in your hands. If you see farther than we did, what wonder—for you stand on our shoulders. We too have our memories and our consolations, and somehow the older we grow, the sweeter the flowers do smell. We have created a new sport for Englishmen. Upon you the responsibility will rest that the future of mountaineering shall be worthy of its present and of its past

Mathews, C. E. (1880/1). The Growth of Mountaineering. In Alpine Journal.

This essay will use the characterisation of modern climbing made by the romantic climbers writing from 1900-1960. This is different to the idea of modern as articulated by Peter H. Hansen in The Summits of Modern Man (2013) and by Caroline Schaumann in Peak Pursuits (2020). For D. L. Hollis, the discovery of the ‘mountain glory’ demarcates the modern, whereas for Young, Irving, Smythe and others it is the obscuring of the ‘mountain glory’ beneath technological, nationalistic and competitive ends that demarcates the modern.

To use a trite analogy: Modern climbing is like attending a concert, filming it on your phone, quantitatively measuring the decibels, beats, notes on an electronic device, logging the songs played in an electronic diary, analysing each word of the songs individually, trying to work out which song is best by analysing these individual words, comparing your recordings with recordings from other concerts, and friends’ concert recordings; all while convincing yourself that this is indeed the whole point of attending concerts.

Romantic climbing is like realising the point of the concert is to experience the concert.

Mathews, C. E. (1900). The Annals of Mont Blanc. L. C. Page & Co. Page 283.

This view of climbing is fully articulated — and labelled as romantic — in R. L. G. Irving's The Romance of Mountaineering (1935) and Frank S. Smythe’s The Spirit of the Hills (1937).

Bartlett, P. (1993). The Undiscovered Country. The Ernest Press.

Heywood, I. (1994). Urgent dreams: climbing, rationalization and ambivalence. In Leisure Studies. Page 186.

Lewis, N. (2004). Sustainable Adventure: Embodied experiences and ecological practices within British climbing. In Understanding Lifestyle Sport.

Bainbridge, S. (2013). Writing from ‘the perilous ridge’: Romanticism and the Invention of Rock Climbing. In Romanticism.

Hollis, D. L. (2019). Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Genealogy of an Idea. In ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment.

Sax, J. L. (1980). Mountains Without Handrails. The University of Michigan Press. Pages 32—3.

Mountaineering, fishing and sailing certainly have things in common, and one very important thing: all of them are the expression of a belief in the inherent good of the outdoors, the worth of communing with an unsullied nature.

Bartlett, P. (2013). Is Mountaineering a Sport? In Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement.

Gill, J. (1979). Bouldering: A Mystical Art Form. In The Mountain Sprit.

The romantics and the Zen Buddhists have different stances towards how to respond to that which is revealed by climbing. Romantics would enthusiastically welcome what is given, whereas the Zen approach would advocate neutrality towards whatever is given — good or bad. I group these approaches together here as has been done previously by Mikel Vause.

Vause, M. (2000). Mountaineering: The Heroic Expression of Our Age. In Personal, Societal, and Ecological Values of Wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress Proceedings on Research, Management, and Allocation, Volume II.

Ilgner, A. (2003). The Rock Warrior’s Way. Desiderata Institute. Page 116.

Abramson, A., & Fletcher, R. (2007). Recreating the vertical: Rock-climbing as epic and deep eco-play. In Anthropology Today.

Firther, G. D. (2008). Wildness, Intensity, Connectivity, and Thereness: A Phenomenological Exploration of Mountain Experience. In The Trumpeter.

Grebowicz, M. (2021). Mountains and Desire: Climbing vs. the End of the World. Repeater. Page 19.

Sanzaro, F, (2023). The Zen of Climbing. Saraband. Pages 11-12.

Wheatley, K. A. (2023). Exploring the relationship between mindfulness and rock-climbing: a controlled study. In Current Psychology.

Djernis, Lerstrup, Poulsen, Stigsdotter, Dahlgaard, & O’Toole. (2019). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nature-Based Mindfulness: Effects of Moving Mindfulness Training into an Outdoor Natural Setting. In International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Choe, E. Y., Jorgensen, A., & Sheffield, D. (2020). Does a natural environment enhance the effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)? Examining the mental health and wellbeing, and nature connectedness benefits. In Landscape and Urban Planning.

Kennedy, H. (2013). Piolets d’Or 2013.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: The expereience of play in work and games. Jossey-Bass.

Mitchell, R. G. (1983). Mountain Experience: The Psychology and Sociology of Adventure. University of Chicago Press. Chapter 11.

Fave, A. D., Bassi, M., & Massimini, F. (2003). Quality of Experience and Risk Perception in High-Altitude Rock Climbing. In Journal of Applied Sport Psychology.

Rickly-Boyd, J. M. (2012). Lifestyle climbing: Toward existential authenticity. In Journal of Sport & Tourism.

Schattke, Kaspar, Brandstätter, Veronika, Taylor, Geneviève, & Kehr, Hugo M. (2014). Flow on the rocks : motive-incentive congruence enhances flow in rock climbing. In International Journal of Sport Psychology.

Brymer, E., & Houge Mackenzie, S. (2016). Psychology and the Extreme Sport Experience. In Extreme Sports Medicine.

Bartlett, P. (1993). The Undiscovered Country. The Ernest Press. Chapter 4.

Lyng calls this enhanced sense of reality ‘hyperreality’ but this is completely different to how Baudrillard uses the word. The way these two thinkers use this word couldn’t be more different, really.

Lyng, S. (Ed). (2004). Edgework: The Sociology of Risk-Taking. Routledge.

Kidder, J. L. (2021). Reconsidering edgework theory: Practices, experiences, and structures. In International Review for the Sociology of Sport.

Lewis, N. (2004). Sustainable Adventure: Embodied experiences and ecological practices within British climbing. In Understanding Lifestyle Sport.

Robinson, D. (1969). The Climber as Visionary. In Ascent.

Mitchell, R. G. (1983). Mountain Experience: The Psychology and Sociology of Adventure. University of Chicago Press. Chapter 10

Vause, M. (1993). Sir Leslie Stephen: The Intrinsic Reward. In On Mountains and Mountaineers. Mountain N’Air Books.

Arzy, S., Idel, M., Landis, T., & Blanke, O. (2005). Why revelations have occurred on mountains? In Medical Hypotheses.

Bainbridge, S. (2013). Writing from ‘the perilous ridge’: Romanticism and the Invention of Rock Climbing. In Romanticism.

Watson, N. J., & Parker, A. (2015). The Mystical and Sublime in Extreme Sports: Experiences of Psychological Well-Being or Christian Revelation? In Studies in World Christianity

Brymer, E., & Houge Mackenzie, S. (2016). Psychology and the Extreme Sport Experience. In Extreme Sports Medicine.

Beer, R. (2017). The Experience of Dying from Falls. In The Robert Beer Blog.

Brymer, E. & Schweitzer, R. (2020). Phenomenology and the Extreme Sport Experience. Routledge. Chapter 11.

Kulczycki, C., & Hinch, T. (2014). “It’s a place to climb”: place meanings of indoor rock climbing facilities. In Leisure/Loisir.

Rickly, J. M. (2017). “I’m a Red River local”: Rock climbing mobilities and community hospitalities. In Tourist Studies.

Brymer, E. & Schweitzer, R. (2020). Phenomenology and the Extreme Sport Experience. Routledge.

Rickly-Boyd, J. M. (2012). Lifestyle climbing: Toward existential authenticity. In Journal of Sport & Tourism.

Hansen, P. H. (2013). The Summits of Modern Man: Mountaineering After the Enlightenment. Harvard University Press. Pages 27—9.

Brymer, E., & Gray, T. (2009). Dancing with nature: rhythm and harmony in extreme sport participation. In Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning.

Brymer, E., & Gray, T. (2010). Developing an intimate “relationship” with nature through extreme sports participation. In Leisure/Loisir.

Crockett, L. J., Murray, N. P., & Kime, D. B. (2020). Self-Determination Strategy in Mountaineering: Collecting Colorado’s Highest Peaks. In Leisure Sciences.

Bourdillon, F. W. (1906/1908). Another Way of (Mountain) Love. In Alpine Journal.

Mitchell, R. G. (1983). Mountain Experience: The Psychology and Sociology of Adventure. University of Chicago Press. Chapter 10.

Karlsen, G. (2010). The Beauty of a Climb. In Climbing - Philosophy for Everyone.

McNee, A. (2016). The New Mountaineer in Late Victorian Britain: Materiality, Modernity, and the Haptic Sublime. Palgrave. Chapter 5.

Schauman, C. (2020). Peak Pursuits: The Emergence of Mountaineering in the Nineteenth Century. Yale University Press. Chapter 1.

Meier, K. V. (1976). The Kinship of The Rope and The Loving Struggle: A Philosophic Analysis of Communication in Mountain Climbing. In Journal of the Philosophy of Sport.

Williams, T., & Donnelly, P. (1985). Subcultural Production, Reproduction and Transformation in Climbing. In International Review for the Sociology of Sport.

Kiewa, J. (2001). Rewriting the heroic script: Relationship in rockclimbing. In World Leisure Journal.

Bartlett, P. (1993). The Undiscovered Country. The Ernest Press. Page 7.

Vervaeke, J., Ferraro, L., & Herrera-Bennett, A. (2018). Flow as Spontaneous Thought. In K. Christoff & K. C. R. Fox (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Spontaneous Thought. Oxford University Press.

Young, G. W. (1958). An Alpine Aura. In Alpine Journal.

Scott, D. (1971). On The Profundity Trail. In Mountain.

Vause, M. (1993). On Mountains and Mountaineers. Mountain N’Air Books.

Vause, M. (2000). John Muir: American Transcendentalist. In The John Muir Newsletter.

Brymer, E. (2009). Extreme Sports as a facilitator of ecocentricity and positive life changes. In World Leisure Journal.

Smuts, J. C. (1923, February 25). The Religion of the Mountain.

Earhart, H. B. (1979). Sacred Mountains in Japan: Shugendō as “Mountain Religion”. In The Mountain Spirit.

Næss, A. (1973). The shallow and the deep, long‐range ecology movement. A summary. In Inquiry.

Næss, A. (2008). Ecology of Wisdom. Counterpoint.

Irving, R. L. G. (1935). The Romance of Mountaineering. J. M. Dent and Sons. Chapter 14.

Irving, R. L. G. (1938). The Mountain Way. J. M. Dent and Sons.

Irving, R. L. G. (1947). The Mountains Shall Bring Peace. Blackwell.

Murray. W. H. (1947). Mountaineering in Scotland. J. M. Dent and Sons. Pages 226—7; 242—3.

Lunn, A. (1948). Mountains of Memory. Hollis and Carter. Pages 232—248.

Ben Garlick contends that some of Nan Shepherd’s writing “present[s] individuals who, in the wake of wartime experience of war, achieve the realization that their personal trauma […] opened them onto being affected in altogether different ways by once familiar landscape”. Conversely, as Philip Bartlett notes, losing his leg in the First World War caused Geoffrey Winthrop Young to lose the mountain rhythm (perhaps, McNee’s haptic sublime) he knew and loved, and this forced him to adjust his philosophy of climbing towards seeking harmony.

Bartlett, P. (1993). The Undiscovered Country. The Ernest Press. Page 83—4.

Garlick, B. (2023). The Total Mountain: Nan Shepherd and the Virtual Qualities of Landscape. In The Mountain and the Politics of Representation. Liverpool University Press.

I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.

My help cometh from the Lord, which made heaven and earth.

Psalm 121 KJV

The mountains shall bring peace to the people, and the little hills, by righteousness.

Psalm 72 KJV

He made him ride on the heights of the land

and fed him with the fruit of the fields.

He nourished him with honey from the rock,

and with oil from the flinty crag.

Deuteronomy 32:13 NIV

Young, G. W. (1957). The Influence of Mountains Upon the Development of Human Intelligence: The seventeenth W. P. Ker memorial lecture delivered in the University of Glasgow, 2nd May, 1956. Jackson, Son & Company.

Nicolson, M. H. (1959). Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite. Cornell University Press.

LaChapelle, D. (1978). Earth Wisdom. Guild of Tutors Press. Chapter 2.

Bernbaum, E. (1990). Sacred Mountains of the World. Sierra Club Books. Chapters 12, 14.

We are Homo sapiens, we are the tool users. We develop tools to increase our leverage on the world around us and with this increased technological leverage comes a growing sense of power. This position of advantage which protects us from wild nature, we call civilisation. Our security increases as we apply more leverage, but along with it we notice a growing isolation from the earth. We crowd into cities, which shut out the rhythms of the planet; daybreak, high tide, wispy cirrus clouds forecasting storms, moonrise, Orion going south for the winter. Perceptions dull and we come to accept a blunting of feeling in the shadow of security. Drunk with power, I find that I am out of my senses again, to bring me nearer to the world once more; in the security I have forgotten how to dance.

So, in reaction, we set sail on the wide sea without motors in hopes of feeling the wind, we leave the Land Rover behind as we seek the desert to know the sun, searching for a remembered bright world. Padding out, we turn to ride the shore-break landward, walking on the wave of smell of wildflowers meeting us on the offshore breeze. In the process we find not what our tools can do for us but what we are capable of feeling without them, of knowing directly. We learn how far our unaided effort can take us into the improbable world. Choosing to play this game in the vertical dimensions of what is left of wild nature makes us climbers.

Chouinard, Y. (1977). Climbing Ice. In Outside Rolling Stone.

Mitchell, R. G. (1983). Mountain Experience: The Psychology and Sociology of Adventure. University of Chicago Press. Page 34.

Heywood, I. (1994). Urgent dreams: climbing, rationalization and ambivalence. In Leisure Studies. Page 186.

Lewis, N. (2000). The Climbing Body, Nature and the Experience of Modernity. In Body & Society.

Lewis, N. (2004). Sustainable Adventure: Embodied experiences and ecological practices within British climbing. In Understanding Lifestyle Sport.

Mitchell, R. G. (1983). Mountain Experience: The Psychology and Sociology of Adventure. University of Chicago Press. Pages 31—6.

Lyng, S. (1990). Edgework: A Social Psychological Analysis of Voluntary Risk Taking. In American Journal of Sociology.

Bartlett, P. (1993). The Undiscovered Country. The Ernest Press. Chapters 4, 5.

Lyng, S. (Ed). (2004). Edgework: The Sociology of Risk-Taking. Routledge.

Lewis, N. (2004). Sustainable Adventure: Embodied experiences and ecological practices within British climbing. In Understanding Lifestyle Sport.

Varley, P. (2006). Confecting Adventure and Playing with Meaning: The Adventure Commodification Continuum. In Journal of Sport & Tourism.

Irving, R. L. G. (1957). Trends in Mountaineering. In Canadian Alpine Journal.

See also: Smart, D. (2019). A Crazy Notion: The Great Dispute, 1911—12. In Paul Preuss: Lord of the Abyss. RMB.

Hansen, P. H. (2013). The Summits of Modern Man: Mountaineering After the Enlightenment. Harvard University Press. Pages 22—3.

Thompson, M. (1980/1983). The Aesthetics of Risk. In Mirrors in the Cliffs. Baton Wicks.

See also: Telford, J., & Beames, S. (2015). Bourdieu and alpine mountaineering. In Routledge International Handbook of Outdoor Studies.

Keen eyed CC readers will note that the Quest and Craft approaches are missing from this diagram and indeed the whole essay. This is just to try and make an already excessively long and complicated essay a little more simple. However, arguably, both Climbing as Quest and Craft are focussing on technical means rather than ends. Sanzaro would call both of these approaches ‘attachments’.

Sanzaro, F, (2023). The Zen of Climbing. Saraband. Page 37.

To characterize climbing shoes and hob-nailed boots as artificial aids in my opinion is a prime example of sophistic quibble. With this same line of reasoning, it ought also in Jacobi’s opinion be considered justified from the alpine and sporting point of view to have a rope ladder tossed down from the summit to get up.

Preuss, P. (1911). Artificial Aid on Alpine Routed [Response to Jacobi]. (R. Burks, Trans.). In The Piton Dispute.

Irving, R. L. G. (1935). The Romance of Mountaineering. J. M. Dent and Sons. Page 121.

For a defence of this argument see Chapter 4? of Mountains Without Handrails.

Mitchell, R. G. (1983). Mountain Experience: The Psychology and Sociology of Adventure. University of Chicago Press. Pages 31—6.

What will the author think of the sixth grade, one day when a tractor with suctiongrips, loaded with first grade climbers, comes steaming past him, as he blacksmiths his way up walls that were best left alone?

Thorington, J. M (1937). “Das Letzte im Fels", by Domenico Rudatis. In American Alpine Journal. Quoted in Smart, D. (2020). Page 136.